RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Dr. Kimo Ori, Department of Community Medicine, Gulbarga Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalaburagi, Karnataka,India.

2Department of Community Medicine, Gulbarga Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India

3Department of Community Medicine, Gulbarga Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India

4Department of Community Medicine, Gulbarga Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Kimo Ori, Department of Community Medicine, Gulbarga Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalaburagi, Karnataka,India., Email: orikimo007@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: For the past few decades, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), has become one of the most significant and quantifiable outcomes of health programs and interventions in public health practice. Furthermore, it has been stressed that the formulation of health care policies must consider pertinent data regarding patient groups’ health conditions as well as public preferences. In this sense, one of the tools used worldwide for evaluating HRQoL in population health is EuroQol 5 dimensions (EQ-5D-5L). Only few countable studies have been done at community level to assess the HRQoL using EQ-5D-5L instrument in India. This study will also help to evaluate the services given by the Urban Field Practice Area (UFPA) thus, the study has been done.

Objective: To assess the health-related quality of life of people residing in Urban Field Practice Area of GIMS, Kalaburagi, Karnataka.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among 80 households of Urban Field Practice Area of Gulbarga Institute of Medical Science (GIMS), Kalaburagi. Systematic random sampling was done to reach the required sample size. A semi structured questionnaire was prepared for collecting Sociodemographic profile. To assess the health-related quality of life EQ-5D-5L instrument was used. After getting ethical Clearance, data collection was done (September-October 2024), entered in MS excel and analysed using Jamovi 2.5.3 software.

Results: The mean EQ index and VAS score 0.901 and 81.1 respectively. EQ index was found to be significantly different among genders (P=0.040).

Conclusion: Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was good among the people residing in the field practice area of GIMS, Kalaburagi.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Health is of utmost significance in individuals’ lives and is a fundamental component of the United Nations’ global sustainable development strategy.1 Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) studies are becoming increasingly prevalent within healthcare systems.2 The World Health Organization (WHO), in its constitution, has defined health as “A state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.2 The WHO’s definition of health acknowledges the significance of health metrics that extend beyond conventional clinical outcomes of morbidity and mortality.3,4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that the metrics of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) have developed since 1980, encompassing elements of Quality of Life (QOL) that demonstrably influence health, whether physical or mental.5 Prominent health organizations have recognized HRQOL as a goal for individuals at all life phases, raising concerns among politicians, researchers, and healthcare practitioners.6 A large body of research has been devoted to development of HRQOL measures.7 Health surveillance has included the use of HRQOL questionnaires, which are regarded as reliable indicators of policy documents, service needs, health needs, and intervention results.5 Over the past ten years, efforts have been made to enhance patient health and the value of healthcare services by increasing the development and use of HRQOL instruments.8

Over the past few decades, health-related quality of life, or HRQoL, has become one of the most significant and quantifiable outcomes of health programs and interventions in modern medicine and public health practice. It is thought to be a trustworthy measure of true improvements in patients’ general health.9 Furthermore, it has been stressed that the formulation of health care policies must take into account pertinent data regarding patient groups’ health conditions as well as public preferences.10 In this sense, one of the most popular tools used worldwide for evaluating HRQoL in clinical, population health, and economic research is the EuroQol 5 dimensions (EQ-5D).11 Only few countable studies have been done at community level and at clinical setting to assess the health related-quality of life using EQ-5D instrument in India. Recently no studies have been done to evaluate the health status or health-related quality of life of people residing in Urban field practice area of GIMS, Kalaburagi, Karnataka. This study will help evaluate the services given by the Urban Field Practice Area, and it will also give an idea about the area of improvement in providing health services. Thus, the objective of the study is to assess the health-related quality of life of people in Urban field practice area of GIMS, Kalaburagi, Karnataka.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting: Urban field practice area of GIMS, Kalaburagi, Karnataka.

Study Population: Household members aged 18 years and above

Study Design: Cross sectional study

Study Duration: 2 months (September to October 2024)

Sample Size: As per the previous study done by Gourav Jyani et al., the SD of EQ index among Indian population was 0.212.11,12 Thus, taking the value of S = 0.212 at confidence interval of 95%, sample size was calculated

Sampling technique: Urban field Practice Area (Manikeswari Colony) has 1633 households. Out of the said households 80 households were selected using systematic random sampling method (Kth value = 82). From the selected households one household member was selected randomly via lottery method to meet the required sample size.

Inclusion Criteria: Randomly selected one household member from the selected household residing in urban field practice area of GIMS, Kalaburagi.

Exclusion Criteria: Household members who were not selected and less than 18 years of age, household locked during the time of visit and household not giving consent.

Data collection and analysis: All participants completed the informed consent document, according to the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical permissions were obtained from the Institutional ethics committee, Gulbarga Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalaburagi, Karnataka (Reg No: ECR/1410/Inst/ KA/2020). Anonymity of the study participants was maintained.

After review of literature semi structure questionnaire was prepared consisting of Sociodemographic profile. To assess the health-related quality of life EQ-5D-5L instrument was used.13,14 Permission for non-commercial use of instrument was taken from the EuroQol website (DocuSign Envelope ID: 0ABD355B-87AC-4B46- 9B90-C5655DC3482E). The EQ‑5D‑5L consists of 2 parts ‑ the EQ‑5D‑5L descriptive system and the EQ Visual Analogue Scale (EQ VAS). The descriptive system comprises the 5 dimensions (mobility, self‑care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression). Each dimension has 5 levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and extreme problems. The investigator first explains the participants how to respond and then asked them to select to indicate his/her health state by ticking in the box against the most appropriate statement in each of the 5 dimensions. This decision results in a 1‑digit number expressing the level selected for that dimension. For EQ VAS the respondents were asked to rate their health on that day on a 20 cm vertical, visual analogue scale from 0 to 100, with endpoints labelled “the best health you can imagine” and “the worst health you can imagine”. This information provides a quantitative measure of health as judged by the individual respondents. The investigator first explains about the tool to the participants and then asked them to mark an X on the scale to indicate how your health is TODAY and then to write the number he/ she marked on the scale in the box below.12 Data was analysed using jamovi 2.5.3.15,16 EQ‑5D‑5L scores was calculated using Indian value set given in EuroQOL website.17 SPSS syntax code for computation of index was used for calculation of EQ index.12,17 Continuous variable was presented in mean and standard deviation, whereas categorical variables in frequency and percentages. EQ‑5D‑5L scores for 5 dimensions and mean EQ VAS scores were compared for age, gender, presence/absence of comorbidities. Correlation between different demographic variables and EQ 5D 5L scores was obtained. P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The mean age of the study participants was 44.9 years. Among the study participants 56.2 % (45) were male and 43.8 % (35) were female.96.2% (77) of participants belonged to Hindu religion and 3.8 % (3) belonged to Muslim religion. 83.8 % (67) of people were married. 72.5 % (58) were Literate, 27.5 % (22) of people in our study were illiterate and 41.3 % (33) of people were unemployed. 31.2 % (25) of household members were of middle class and 78.8 % (63) were residing in pucca house (Table 1).

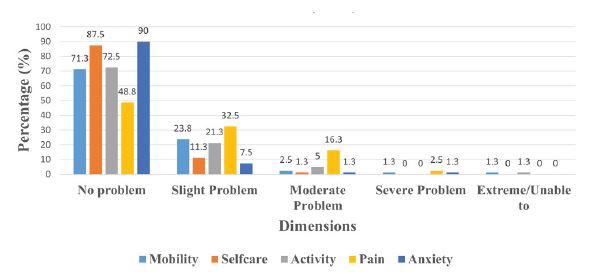

The highest proportion of participants reported no problems in the anxiety/depression (90%, 72) and selfcare (87.5%, 70) dimensions. Activity (72.5%,58) and mobility (71.3%, 57) had slightly lower proportions, while pain was reported as a no concern by 48.8% (39) of participants. The most frequently reported slight problem was pain (32.5%, 26), followed by mobility (23.8%, 19). A smaller proportion of respondents experienced self-care (11.3%,9), anxiety/depression (7.5%, 6), and activity (21.3%, 17) problems. Pain remained the most affected domain, with 16.3% (13) of respondents reporting moderate issues. Activity was the next most common moderate issue at 5% (5). Mobility, self-care, and anxiety/depression had lower reports, at 2.5% (2), 1.3% (1), and 1.3% (1), respectively. The highest proportion of severe problem was in pain, with 2.5% (2) of respondents affected. Severe mobility and anxiety/ depression issues were reported by 1.3% (1), whereas no severe self-care issues were recorded. Only 1.3 % (1) participants reported extreme problems or being unable to perform tasks mobility and activity (Figure 1). The mean EQ index among the studied population was 0.901 ± 0.154. Mean VAS score was 81.1 ± 12.5 (Table 2).

A significant decline in the EQ index was observed with increasing age (P = 0.007). Participants aged 18-40 had the highest mean EQ index (0.953), while those aged >60 had the lowest (0.772). Males reported a significantly higher EQ index (0.938) than females (0.854), with a P-value of 0.040. Married individuals had a slightly higher mean EQ index (0.909) than single, widowed, or divorced participants (0.862), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.565). No significant difference was found between Hindu (0.902) and Muslim (0.890) participants in terms of HRQoL (P = 0.793). Literate participants had a higher EQ index (0.925) compared to illiterate individuals (0.838), though the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.096). Employment status did not show a significant impact on HRQoL (P = 0.262). The highest EQ index was reported among private-sector employees (0.952), while non-employed individuals had the lowest (0.857). Participants from nuclear families had the highest mean EQ index (0.920), followed by joint families (0.880) and three-generation families (0.835). However, the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.568). A significant difference in HRQoL was observed based on housing type (P < 0.001). Participants living in pucca houses had a significantly higher EQ index (0.936) than those in semi-pucca houses (0.773), highlighting the impact of living conditions on quality of life. Higher socioeconomic status was associated with better HRQoL, though the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.763). The highest EQ index was reported among upper-class participants (0.914), while the lowest was among the lower-class group (0.841). No significant association was found between substance abuse and HRQoL (P = 0.226), though those who did not use substances had a slightly lower EQ index (0.916) compared to those who reported substance use (0.894). The presence of ailments had a significant negative impact on HRQoL (P < 0.001). Participants with chronic illnesses had the lowest EQ index (0.815), while those with no reported ailments had the highest (0.947). Acute illnesses also negatively impacted HRQoL (EQ index = 0.879) (Table 3).

The study found that age significantly influenced VAS scores (P = 0.005), with participants aged 18- 40 years having the highest mean score of 84.3 (SD = 13.2), followed by those aged 41-60 years at 80.3 (SD = 11.1), and participants aged below 60 years scoring the lowest at 72.9 (SD = 10.3). Gender did not show a significant difference (P = 0.583), with males having a mean score of 82.0 (SD = 11.7) and females 79.9 (SD = 13.6). Marital status was also not a significant factor (P = 0.208), with married participants scoring 81.6 (SD = 13.1) and single/widowed/divorced participants scoring 78.3 (SD = 8.4). The type of family was not a significant factor (P = 0.905), with joint families scoring 81.3 (SD = 10.9), nuclear families 81.0 (SD = 13.5), and three-generation families 79.7 (SD = 17.0). However, the type of house showed a significant difference (P = 0.009), with those living in Pucca houses scoring higher at 82.8 (SD = 12.7) compared to those in Semi Pucca houses at 74.7 (SD = 9.2). Socioeconomic status did not significantly impact VAS scores (P = 0.964), with upper-class individuals scoring 80.9 (SD = 11.9), upper-middle class 81.1 (SD = 12.7), middle class 80.3 (SD = 13.6), lower-middle class 81.3 (SD = 14.1), and lower class 80.6 (SD = 12.3). However, the presence of ailments showed a highly significant difference (P < 0.001), with participants having acute ailments scoring 80.2 (SD = 10.8), those with chronic ailments scoring the lowest at 70.6 (SD = 13.5), and those without ailments scoring the highest at 86.0 (SD = 10.5) (Table 4).

Age was negatively correlated with EQ Index (- 0. 386, P < 001) and VAS score (- 0.305, P = 0.006). VAS scoreand EQ Index were moderately correlated (0.466, P < 0.001). There was a negative correlation between type of house and EQ index (-0.443, P < 0.001), as the quality of house declined EQ index also declined (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study aimed to assess the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of individuals residing in the urban field practice area of GIMS, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, using the EQ-5D-5L instrument. The findings revealed that the mean EQ index among the studied population was 0.901 (±0.154), while the mean VAS score was 81.1 (±12.5). These results indicate a relatively good perceived quality of life among the study population, with variations observed across different sociodemographic variables.

A study conducted by Tabassum Wadasadawala et al. among breast cancer patients and non-cancer subjects at Tata Memorial Center (TMC), Mumbai, found that cancer patients had a significantly lower EQ-5D-5L utility score (0.8703 at baseline) compared to non-cancer subjects (0.93, P < 0.000).18 In contrast, the current study’s participants, comprising the general population, had a higher mean EQ index (0.901), indicating a better HRQoL than cancer patients but somewhat lower than the non-cancer cohort in the Mumbai study.

Similarly, a large-scale cross-sectional survey conducted by Jyani G et al. in five Indian states reported a mean EQ-5D-5L utility score of 0.849 (±0.212) and a mean EQ VAS score of 75.18 (±16.42).12,19 Compared to these findings, the present study observed higher mean scores for both the EQ index and VAS, suggesting a better self-reported health status among the urban population of Kalaburagi. However, the distribution of problems was similar, with the highest burden reported in pain/ discomfort (32.5% slight problems, 16.3% moderate problems) and mobility (23.8% slight problems). These findings align with Jyani et al.’s study, where pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression were the most commonly reported issues.12,19

Another study by Mohammad Reza Abedini et al. among type 2 diabetes patients in Birjand, Iran, reported a mean EQ-5D-5L score of 0.89 (±0.13) and an EQ VAS score of 65.22 (±9.32).20 The lower VAS score in their study compared to the present study (81.1) suggests that individuals with chronic diseases experience a lower perceived quality of life. Similarly, our study also observed that individuals with chronic illnesses had the lowest EQ index (0.815) and VAS scores (70.7, P < 0.001), reinforcing the negative impact of chronic conditions on HRQoL.

A study by Paresh C et al. conducted in a tertiary care hospital in India among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients found that the EQ-5D-5L scores were significantly lower among those with comorbidities, particularly hypertension.21Our study also confirmed this trend, as the presence of ailments significantly impacted HRQoL (P < 0.001). This underscores the importance of managing chronic conditions to improve quality of life.

Impact of Sociodemographic Factors

The study found that age significantly influenced HRQoL, with older individuals (>60 years) reporting lower EQ indices (0.772) and VAS scores (72.9) than younger age groups (P = 0.007). This is consistent with previous studies indicating that aging is associated with decreased physical and mental health, thereby reducing overall quality of life.

Gender disparities were also observed, with males reporting significantly higher EQ indices (0.938) than females (0.854, P = 0.040). This aligns with previous findings that women tend to report lower HRQoL due to higher burdens of caregiving, stress, and health conditions. Similarly, literacy was associated with a higher EQ index (0.925 for literate vs. 0.838 for illiterate), though the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.096). This suggests that education may contribute to better health awareness and access to healthcare.

Housing conditions significantly affected HRQoL, as individuals residing in pucca houses had higher EQ indices (0.936) and VAS scores (82.8) compared to those in semi-pucca houses (0.773, P < 0.001). This finding supports the link between living conditions and well-being, as better housing is associated with improved hygiene, security, and mental health.

Limitation

The study does not include population less than 18 years as the instrument used in the study is applicable to 18 plus population.11 Furthermore, preference of population to private or govt health sector can be also an influencing factor in health-related quality of life which was not assessed in the current study.

Conclusion and Implications

The study highlights the overall good HRQoL of individuals in the urban field practice area of GIMS, Kalaburagi. However, significant disparities exist across age, gender, health conditions, and living conditions. The findings emphasize the need for targeted healthcare interventions, particularly for the elderly, individuals with chronic illnesses, and those in suboptimal living conditions. Strengthening primary healthcare services and addressing socioeconomic determinants can further enhance HRQoL in urban communities.

Future research should expand the sample size and explore longitudinal trends to assess the impact of healthcare policies and interventions on HRQoL over time.

Ethical Clearance

Taken from the Institutional Ethics Committee, GIMS, Kalaburagi on 10th September, 2024 (Approval Letter No. GIMS/PHARMA/IEC/298/2024-25)

Financial support and funding

Nil

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to extend their deep gratitude to Basavaraj Gouda, Health Inspector and Arvind Patil, Medical Social Officer for their contribution in data collection in the field.

Supporting File

References

1. D R, R S, Manjunath U. Quality of life among community health workers in the districts of Koppal, Raichur and Mysore, Karnataka State, India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2024 Aug; 29 (3): None. Doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2024.101752

2. Johnson JA, Coons SJ. Comparison of the EQ5D and SF 12 in an adult US sample. Quality of Life Research 1998;7(2):155-166.Doi: 10.1023/A:1008809610703

3. World Health Organization: Division of Mental Health and Prevention of Substance Abuse. WHOQOL and spirituality, religiousness and personal beliefs (SRPB). 1997,

4. Ramchandran V, Malaisamy M, Ponnaiah M, Kaliaperuaml K, Vadivoo S, Gupte MD. Impact of Chikungunya on Health Related Quality of Life, Chennai, South India. PLOS one 2012; 7(12):1-7. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051519

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health Related Quality of Life Concepts. (2022). Accessed: December 9, 2024: https://archive.cdc. gov/www_cdc_gov/hrqol/index.htm.

6. Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, Buelow JM, Otte JL, Hanna KM, et al. Systematic review of health related quality of life models. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2012;10(1):1-12.Doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-134

7. Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross Cultural Adaptation of Health Related Quality of Life measures: Literature Review and Proposed Guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46(12):1417- 1432. Doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-N

8. Varni JW, Burwinke TM, Lane MM. Health related quality of life measurement in paediatric clinical practice: An appraisal and precept for future research and application. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2005 ; 3(1):34. Doi: 10.1186/1477-7525- 3-34

9. Kind P, Hardman G, Leese B. Measuring health status: information for primary care decision making. Health Policy 2005 ; 71(3):303-313. Doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.02.008

10. Santos M, Monteiro AL, Santos B. EQ-5D Brazilian population norms. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021 ;19(1):162. Doi: 10.1186/s12955-021-01671- 6

11. EuroQol Research Foundation: EQ-5D-5L User Guide. 2019. https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides.

12. Jyani G, Prinja S, Garg B, Kaur M, Gorver S, Sharma A, et al. Health-related quality of life among Indian population: The EQ-5D population norms for India. J Glob Health 2023; 13:04018. Doi: 10.7189/ jogh.13.04018

13. EuroQol. Available versions -. EuroQol [Internet]. EuroQol. 2025,

14. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five‑level version of EQ‑5D (EQ‑5D‑5L). Qual Life Res 2011 ; 20(10):1727- 1736. Doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x

15. The jamovi project (2024). jamovi: Version. 25. https://www.jamovi.org.

16. R Core Team (2023). R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.3) [Computer software]. (2023). Accessed: 2024-01- 09: https://cran.r-project.org.

17. EuroQol. Value sets - EuroQol [Internet]. EuroQol. 2025. https://euroqol.org/information-andsupport/ resources/value-sets/.

18. Wadasadawala T, Mohanty S, Sen S, Khan PK, Pimple S, Mane JV, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) Using EQ- 5D-5L: Value Set Derived for Indian Breast Cancer Cohort. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2023; 24(4):1199- 1207. Doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2023.24.4.1199

19. Jyani G, Prinja S, Kar SS, Trivedi M, Patro B, Purba F, et al. Valuing health-related quality of life among the Indian population: a protocol for the Development of an EQ-5D Value set for India using an Extended design (DEVINE) Study. BMJ Open 2020; 10(11): e039517. Doi: 10.1136/ bmjopen-2020-039517

20. Abedini MR, Bijari B, Miri Z, Emampour FS, Abbasi A. The quality of life of the patients with diabetes type 2 using EQ-5D-5 L in Birjand. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020 ; 18(1):18. Doi: 10.1186/ s12955-020-1277-8

21. Parikh PC, Patel VJ. Health-related quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at a tertiary care hospital in India using EQ 5D 5L. Indian J Endocrinol Metab.2019; 23(4):407-411. Doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_29_19