RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Paalana Institute of Medical Sciences, Paalana Hospital, Palakkad, Kerala, India

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Yadgiri Institute of Medical Sciences, Yadgiri, Karnataka, India

3Dr. Shruti Kardalkar, Associate Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Karuna Medical College and Hospital, Palakkad, Kerala, India.

4Department of Community Medicine, ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Gulbarga, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Shruti Kardalkar, Associate Professor, Department of Community Medicine, Karuna Medical College and Hospital, Palakkad, Kerala, India., Email: drshru.kardalkar@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Gender preference, a social milieu, remains a pertinent public health predicament globally. About 140 million women around the world are believed to be missing due to gender-biased sex selection and male preference. After the 1990s, a few regions in the world reported up to a 25 percent increase in male births compared with female births. Gender preferences and their determinants have changed recently, with higher male preference, especially in developing countries. The newly released National Family Health Survey (NFHS- 5) reconfirms that a large number of Indians preferred sons. The current situation is appalling, and gender imbalance has a damaging effect on societies.

Objectives: The study was conducted to determine gender preferences among married adult men and to identify associated factors.

Methods: A cross-sectional, descriptive, epidemiological mixed-methods study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Karnataka. Sociodemographic details were quantified, and one-on-one interviews were conducted for qualitative aspects. Data were collected from married men aged 18-45 years, selected through purposive sampling, after obtaining informed consent and assuring anonymity and confidentiality. Findings were represented as percentages, Chi-square test results, and verbatim quotes from the study participants.

Results: A total of 216 married men participated in the study. Among them, 43.04% were aged 25-31 years, 47.22% were literates, and the majority belonged to the middle-class socioeconomic status and nuclear families. Significant factors associated with gender preference were residing in rural areas and living in joint families (P <0.05). The preferred gender was highly influenced by the choices of spouses and family members. The common perception favoured a male child irrespective of birth order, driven by family pressure.

Conclusion: Despite numerous campaigns and awareness initiatives over the years, the preference for sons remains strong among Indian families. Even today, society continues to reward birth of a son, making it an uphill task in India to bring about changes in mindset and social values that are urgently required to address gender imbalance.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Gender preference, a social milieu, remains a pertinent public health predicament globally. About 140 million women around the world are believed to be missing due to gender-biased sex selection and male preference.1 Gender preferences and their determinants have changed recently, with higher male preference, especially in developing countries. After the 1990s, a few regions in the world reported up to a 25 percent increase in male births compared with female births. The desire for a male child was exacerbated by cultural practices and norms in these countries.2,3 Even after 76 years of independence, the preference for a male child in Indian households persists, as over eight percent of households report that they would prefer to have at least one male child in their lifetime.2 The newly released National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) reconfirms that a large number of Indians (80%) preferred sons.4

Sex ratio is an important social indicator for measuring the extent of prevailing equity between males and females in the society.5 Female feticide, resulting in a decline of the child sex ratio, led the Government of India to pass the Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act (PNDT) in 1994. This law was further amended into the Pre-Conception and Pre- Natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) (PCPNDT) Act in 2004, to deter and punish prenatal sex screening and female feticide.6 A declining sex ratio highlights the poor socio-economic, cultural, and politico-legal framework in society. It indicates male child preference, low status of women, prevalence of dowry, illegal sex determination of foetus in-utero, and illegal abortions.5 As per the latest Census (2011), the total female sex ratio in India is 940 females per 1000 males and the female child sex ratio is 944 girls per every 1000 boys of the same age group. The overall female sex ratio has increased by 0.75% in Census 2011 compared to Census 2001.7 As per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS–5), the sex ratio at birth for children born in the last five years in India is 929 females per 1000 males.8

A couple’s gender preference for children is usually influenced by traditional background, cultural practices, and patriarchal gender norms passed down over generations. The reasons for male gender preference commonly include representing the social status of the family, supporting and inheriting the family business, and continuing the family lineage.9 A strong desire for a male child also results in repeated and closely spaced pregnancies, premature deaths, and even termination of the child before birth.6,10,11

A female child is often considered an added responsibility. Old-age dependency, family status, women’s safety concerns, marriage expenses like dowry practices, and the belief that daughters will not stay with their parents after marriage, are some of the factors that influence non-preference for daughters.9,12

Gender preference has predominantly been evaluated among antenatal women. However, married men also play a pivotal role in deciding the ideal family size and the preferred gender of the child. Gender preferences and their determinants have changed in recent years, with an increasing inclination toward male preference, particularly in developing nations. The current situation is appalling, and gender imbalance has a damaging effect on societies.

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) data (2007), “for more than 100 years, the Indian census has shown a marked gap between the number of boys and girls, men and women. This gap, which has nationwide implications, is the result of decisions made at the most local level-the family”.2

Considering the above overview, this study was conducted to determine gender preferences among married men and to identify the associated factors.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This mixed-methods study (quantitative and qualitative) was conducted over a period of three months, from July to September 2022, at a tertiary care hospital in Karnataka, among adult married men who were accompanying their spouses to the antenatal clinic.

Sample Size

The sample size considered was 216. (The total number of study participants over three months was approximately 250; due to incomplete data, 34 were not included in the final analysis)

Sampling Procedure

Data were collected from adult married men who were accompanying their spouses to the antenatal clinic of a tertiary care hospital.

Inclusion Criteria

Married men who consented to participate in the study on a voluntary basis, accompanying their spouses, where the spouse was either primigravida, nulliparous, or nulligravida, were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Married men whose spouses were multigravida, had a bad obstetric history, existing chronic illness, or were presenting in emergency labour were excluded.

Study Instrument

The study instrument comprised basic sociodemographic details and factors related to gender preference.

Data Collection

Data were collected from 216 married men using a pre-designed, pre-tested proforma and questionnaire. The questionnaire was distributed to the study participants and included their sociodemographic profile and marital characteristics, which were used for the quantitative analysis. The questionnaire used in the study was translated into the vernacular language and validated by the investigators. Data were collected after obtaining written informed consent on a voluntary basis, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality.

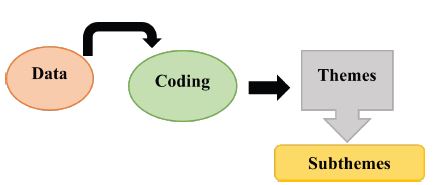

Quantitative Analysis - Theme and Subtheme Generation

Ten percent of the total sample size was considered for quantitative analysis. One-on-one interviews were conducted with every 10th study participant to explore gender preference among married men, as this provided the required number of interviews within the available time and resources.13 The discussions were handwritten; transcripts were read, re-read, and then coded. Codes with similar meanings were noted, grouped together to generate themes and subthemes relevant to the study objectives. The findings were presented with verbatim quotes from the participants. The themes generated were related to the reasons for gender preference.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered in an Excel sheet and analysed using SPSS version 22.0. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages were calculated, and the Chi-square (χ2) test was applied to determine the association between two attributes. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Convenience sampling of 250 participants was initially considered; however, 34 participants submitted incomplete proformas, which were not included in the final analysis. Hence, the sample size was 216.

Table 1 depicts the sociodemographic details of the study participants (n=216). About 43.05% were aged 25-31 years, 56.94% were from rural areas, and 47.22% were literates. The majority (46.76 %) were residing in nuclear families, and 73.61% of the participants belonged to the middle-class socioeconomic status as per the Modified B G Prasad Classification, 2021.14

Table 2 shows the association of gender preference among married men with sociodemographic factors and other variables. Various factors were evaluated for gender preference. Residing in joint families, belonging to a rural background, agreeing to the decision of family members, and being the only male child in the family were found to be significant factors (P <0.05). Other factors influencing gender preference included consanguineous marriage and education status of the study participants.

Qualitative Analysis

Ten percent of the study participants were considered for qualitative analysis. A total of 21 participants were interviewed, of whom 42.85% were aged 25-31 years, 66.67% were from rural areas, and the majority (57.14%) belonged to joint families.

Table 3 presents the verbatims of the study participants generated through qualitative analysis. The verbatim quotes primarily related to family lineage and security in old age.

Table 4 illustrates the qualitative analysis for the generation for themes and subthemes for gender preference among the study participants. The reasons for gender preference were generated through thematic analysis. The one-on-one interview transcripts were read, re-read, the codes were used to generate themes for explaining the reasons for gender preference. The themes generated are as follows:

Theme 1: Wish of family

Married men expressed that the desire of family members and their spouse to have a male child indirectly influenced their own decision.

Theme 2: A girl child is an additional responsibility

A girl child was perceived as an additional responsibility due to concerns related to education, marriage and dowry, security, and burden of expenses to bear throughout life, which influenced the preference for sons over daughters.

Theme 3: Carrying forward the family lineage

Married men conveyed that carrying forward the family name was the most important aspect for their family and themselves, contributing to gender preference disparity.

Theme 4: Females are more responsible

A few married men who preferred a female child stated that females are more responsible, adjusting, obedient, caring, and provide better emotional support than a male child.

Discussion

Gender preference has predominantly been evaluated among antenatal women. There are very few studies that have assessed gender preference among married men. Some studies evaluating gender preference among antenatal women have included the opinion of their partners as well.

A study done by Saha R in West Bengal in 2019 found that 66.4% of participants were from rural areas and 90% belonged to the lower socio-economic status (according to the Modified B. G. Prasad Scale, 2015).6 In contrast, in our study, 56.94% hailed from rural areas, the majority (53.70%) were residing in nuclear families, and 73.61% belonged to the middle-class socioeconomic status as per the Modified B G Prasad classification, 2021.14

In this study, married men were interviewed. It was found that 61.57% of them had a gender preference (male child), which is comparable to a study done by Saha R in West Bengal in 2019, where 77% of partners of antenatal women preferred a male child.6

In the present study, only married men whose spouses were primigravida were interviewed, because having an existing child could influence gender preference in subsequent pregnancies. It was found that married men preferred a male child, and this preference was highly influenced by the decisions of spouses and family members. Participants expressed that they agreed to the preference of a male child because their family desired it, and they felt compelled to accept these opinions.

In our study, married men living in rural areas had gender preference for a male child which was statistically significant. This can be attributed to the dominant patriarchal culture norms in rural areas, which are reinforced by low education levels, lack of employment opportunities for women, and the culture of carrying forward the family lineage.

The present study also concluded that married men from joint families had a greater preference for a male child. This was largely influenced by the members in the family. In a joint family, there is often a preference for a male child irrespective of the birth order.

Being the only male child in the family was also a contributing factor for preferring a male child, as the responsibility of carrying forward the family lineage was emphasized.

Comprehensively, it was found that the reasons for preferring a male child among married men included pressure from family members, the perception that a girl child comes with additional responsibilities, and the desire to continue the family lineage.

Conclusion

This study reflects a persistent preference for sons among married men, highlighting the continuing existence of gender preference. It concluded that the preference for a male child was greatly influenced by family decisions and the desire to continue for the family hierarchy.

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our understanding, this was a unique attempt to evaluate gender preference among married men, considering the fact that men also play an important role in determining the family size and structure. The present study followed a systematic and précised strategy to obtain relevant data in line with the research objectives.

Nevertheless, few limitations were noted. The findings were based on a self-reported questionnaire rather than direct observations; hence, some degree of response bias cannot be excluded. Furthermore, the qualitative analysis involved a limited number of study participants (10% of the total sample), which restricts the generalizability of the results to the wider community. However, despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the gender preference among married men.

Conflict of Interest

Nil

Source of Funding

None

Acknowledgement

We thank all the participants who took part in the study.

Supporting File

References

1. Shrivastava N, Soni GP, Shrivastava S, et al. Study on gender preference and awareness regarding prenatal sex determination among married women of reproductive age group in urban slums of Raipur city. Int J Med Sci Public Health 2020;9(2):170- 173.

2. Indians prefer sons over daughter. Times of India. [cited 2022 Dec 23]. Available from: https://www. indiatimes.com/news/india/indians-prefer-sons-over-daughters-nfhs5-survey-569915.html

3. Saya GK, Premaranjan KC, Roy G, et al. Extent of difference between male and female gender preference and associated factors among currently married women of reproductive age group in Puducherry, India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2021;100692:1-6.

4. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. National Family Health Survey (NFHS- 5) 2019-2021: Compendium of fact sheets – Key indicators. New Delhi: MoHFW, GOI; 2021 [cited 2022 Nov 25]. Available from: https://main.mohfw. gov.in/sites/default/files/NFHS-5_Phase-II_0.pdf

5. Chellaiyan VG, Adhikary M, Das TK, et al. Factors influencing gender preference for child among married women attending ante-natal clinic in a tertiary care hospital in Delhi: a cross-sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Health 2018;5:1666-70.

6. Saha R. Biasness in gender preference among the antenatal mothers: An institute based mixed method study in Eastern India. Int J Prev Curat Comm Med 2019;5(1):16-21.

7. Katkuri S, Kumar KN. Gender preference and awareness regarding sex determination among married women in urban slums. Int J Community Med Public Health 2018;5:987-90.

8. Patel HR, Patel RR. Study on gender preference among pregnant women attending the tertiary care hospital, Valsad: A cross-sectional study. J Community Health Manag 2022;9(3):131-135.

9. Preethi AM, Geethalakshmi RG, Prakash K. A study on perception for gender preference among married women of urban field practice area of a medical college in Davangere, Karnataka. Ann Community Health 2021;9(2):177-181.

10. Rawat S, Yadav A, Parve S, et al. Epidemiological factors influencing gender preference among mothers attending under-five immunization clinic: A cross-sectional comparative study. J Educ Health Promot 2021;10(1):190.

11. Puri S, Bhatia V, Swami H. Gender preference and awareness regarding sex determination among married women in slums of Chandigarh. Indian J Community Med 2007;32(1):60-2.

12. Bhattacharjya H, Das S, Mog C. Gender preference and factors affecting gender preference of mothers attending antenatal clinic of Agartala Government Medical College. Int J Med Sci Public Health 2014;3:137-139.

13. Francis R, Micheal C, Patricia C. Interviewing in qualitative research. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 2009;16(6):309-313.

14. Sharma N, Aggarwal P. Modified BG Prasad socioeconomic classification, update – 2021. J Integr Med Public Health 2022;1:7-9.