RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Nani Gopal Tripura, Professor, Department of Radiology, Shantiniketan Medical College, Agartala, Tripura, India.

2Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Consultant, ILS Hospital, Agartala, Tripura, India

3Department of Internal Medicine, Consultant, ILS Hospital, Agartala, Tripura, India

*Corresponding Author:

Nani Gopal Tripura, Professor, Department of Radiology, Shantiniketan Medical College, Agartala, Tripura, India., Email: nanigopal69@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: COVID-19 has varied clinical presentations, and severity is often assessed by chest computed tomography (CT) imaging findings. Chest CT severity scoring has emerged as a tool for evaluating disease extent and correlates with clinical parameters.

Objective:To examine the correlation between chest CT severity scores and clinical parameters in COVID-19 patients in North Eastern India.

Methods: This descriptive study included 250 patients with COVID-19. Demographic data, clinical history, comorbidities, and biochemical markers (CRP, ESR, WBC, D-dimer, and serum ferritin) were collected from medical records. Chest CT severity was classified as mild (<8), moderate (9–15), or severe (>15). Associations between CT severity scores and patient demographics, comorbidities, symptom duration, and laboratory markers were analyzed using Chi-square tests and logistic regression; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results: Most patients were male (64%), with a mean age of 54.3±16.5 years; the majority (68%) were aged 41–80 years. The most common comorbidities were diabetes mellitus (19%) and hypertension (12%). Severe CT severity scores were observed in 54% of patients, moderate in 29%, and mild in 17%. Higher CT severity scores were significantly associated with older age (P=0.03), presence of comorbidities (P=0.01), longer symptom duration (P=0.02), and a history of COVID-19 infection (P=0.04). Elevated inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and D-dimer were also prevalent among those with severe CT scores.

Conclusion: This study highlights the clinical relevance of CT severity scoring in managing COVID-19 patients, particularly in settings where rapid risk assessment is critical.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Since December 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has led to an unparalleled global health crisis.1 Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), severe pneumonia, multiorgan failure, as well as mild to moderate respiratory symptoms, are among the clinical manifestations observed during the COVID-19 illness.2 COVID-19 has placed an immense burden on healthcare systems globally, with significant morbidity and mortality reported across diverse populations, specifically in India.3 As of April 2024, India reported 45 million confirmed cases and half a million deaths due to COVID-19.4

This highly infectious viral disease has an incubation period ranging from two and fourteen days. Although reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) remains the gold standard for COVID-19 detection, its diagnostic utility is constrained by the time required for sample transport and material preparation, leading to significantly delayed results.5 The severity of COVID-19 also varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic infection to critical illness requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mechanical ventilation. Several clinical parameters, including age, comorbidities (such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity), and laboratory findings (such as lymphopenia, elevated inflammatory markers, and abnormal coagulation profiles), have been identified as predictors of disease severity and adverse outcomes.6 However, the role of radiological imaging in assessing disease severity and predicting clinical outcomes in COVID-19 remains an area of active investigation. Chest computed tomography (CT) is a quick, readily available imaging modality that can support the diagnosis of COVID-19, particularly in settings where laboratory resources are overwhelmed.7

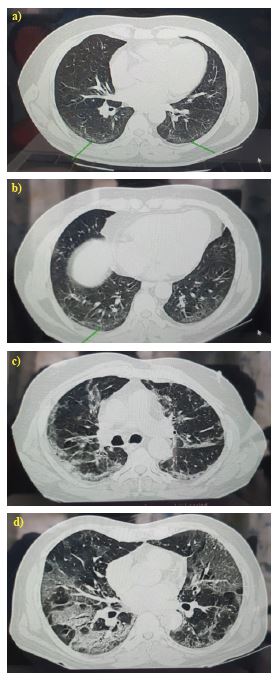

Recent studies have reported that most patients with COVID-19 disease exhibit typical radiologic features on chest CT scans. These features commonly include bilateral ground-glass opacities in the lower lobes, with a posterior or peripheral distribution, which progress to a crazy-paving pattern and eventually to areas of consolidation.8 Moreover, imaging results can be used to evaluate the disease's prognosis and severity, assisting physicians in timely clinical decision-making. Therefore, this study was undertaken to fill the lacunae in the current literature.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Study Setting

A retrospective descriptive analysis of available medical records was conducted in the Department of Radiology between October 2020 and October 2021 at a tertiary care institute in Tripura, Eastern India. A waiver of informed consent was granted, as the study involved a review of existing records, and strict confidentiality of patient information was maintained. The study proposal was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board.

Study Participants

A total of 250 medical records with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19, defined by the World Health Organization as a positive RT-PCR, and who underwent CT investigation during the study period were included.9 Patients with only a clinical diagnosis of COVID-19, a history of lung cancer or prior lung surgery, pregnant patients, and those with a known diagnosis of viral or bacterial pneumonia were excluded. Using estimates from Sharma et al., where the proportion of severe COVID-19 based on the CT severity score (CTSS) was reported as 58%, with 7% absolute precision, and a 95% CI, the required sample size was calculated to be 191. Considering a 20% non-response rate, the final sample size was calculated to be 229. Ultimately, 250 records meeting the inclusion criteria were analyzed.

Study Tool

A semi-structured data collection proforma was employed to record sociodemographic characteristics, clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, comorbidities, radiological features, and CT severity score. Relevant data obtained from the hospital information system and patient records were directly entered into the data collection proforma, which was maintained in Microsoft Google Sheets.

Study Procedure

The study was undertaken after obtaining ethical approval from the Institute Ethics Committee. All collected patient records were deidentified, and confidentiality was maintained throughout the study. A GE Optima 660 was used to obtain the CT images. Axial chest CT images were acquired first, followed by multiplanar reconstruction in the sagittal and coronal planes. Patients were scanned in the supine position, and a slice thickness of 0.625 - 1.250 mm with same increment was used to reconstruct the images. The parameters maintained are listed in Table 1.

All relevant blood investigation profiles of the patients at the time of admission were also retrieved and correlated with the CT severity scores.

The CT images were analysed by the investigators to identify typical features of COVID-19 pneumonia, which include subpleural unilateral or bilateral ground-glass opacities (GGOs) in the lower lobes with a peripheral or posterior distribution. These findings may progress to a crazy-paving pattern and subsequently to consolidation.10 Taking into account the degree of anatomic involvement, a semiquantitative CT severity score, as suggested by Pan et al.,was determined for each of the five lobes.10,11

Each of the two left and three right lung lobes was assessed separately, and the percentage of lobar involvement was visually estimated. A total score of 25 was obtained by classifying the visual severity scoring of the CT chest into five categories: Score-1 (less than 5% area involved), Score-2 (5-25% area involved), Score-3 (25-50% area involved), Score-4 (50-75% area involved), and Score-5 (more than 75% area involved). CT severity score for each case was obtained by summing the individual lobe scores, yielding a value ranging from 0 (nil involvement) to 25 (maximum involvement)].9,10

Statistical Analysis

Data were collected in Google Sheets, and subsequently exported to Microsoft Excel. Data entries was double-checked by the investigators to ensure quality. Continuous variables were summarized as mean±SD or median with interquartile range (IQR), based on normality. All qualitative data were summarized as frequencies and proportions. The Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative data, while the unpaired T test (for parametric data) or the Mann-Whitney U test (for non-parametric data) was applied to assess associations with qualitative data. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Data from 250 patients records that met the eligibility criteria and contained complete information were included in the analysis. Demographic and baseline clinical parameters are summarized in Table 2. Majority of the study participants (68%) were within the 41-80 year age group, with a median (IQR) age of 50 (34- 68) years. Males constituted about 64% of the study population. Diabetes mellitus (19%) emerged as the most frequently observed comorbidity, followed by hypertension (12%). Approximately 7% of patients were asymptomatic at presentation, while more than half (52%) reported symptoms lasting for more than a week. A previous history of COVID-19 infection was noted in 25% of the participants. The distribution of biochemical blood parameters among the study population is presented in Table 3. Elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), white blood cell (WBC) count, D-dimer, and serum ferritin were observed in 80%, 70%, 50%, 62%, and 30% of participants, respectively.

Table 4 presents the distribution of CT severity scores among the study participants. More than half of the participants (54%) demonstrated severe CT severity scores, while 29% had moderate scores, and the remaining 17% exhibited mild scores.

Table 5 presents the association between the CT severity score and the demographic and clinical parameters of the study participants. A significant association was observed between CT severity score and age, with higher CT severity scores noted in older individuals (P=0.03). The presence of comorbidities was also associated with severe CT scores (P=0.01). In addition, longer duration of symptoms (P=0.02), and a past history of COVID-19 (P=0.04) also showed a significant association with severe CT scores.

The various radiological patterns observed among the patients are illustrated in Figure 1.

Discussion

A descriptive record review was conducted using available clinical records of patients with confirmed COVID-19 in North Eastern India to determine the association between CT severity scores and demographic and clinical characteristics. The findings indicate that age, comorbidity status, symptom duration, and past history of COVID were significant determinants of CT severity scores.

The findings from this study align with previous research conducted elsewhere. In particular, studies from China by Shang et al., (2020) and Xu et al., (2020) demonstrated that older age groups (>60 years) and patients with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension tend to exhibit more severe CT severity scores.12,13

The high proportion of severe CT severity scores observed in the present study (54%) may be attributable to the fact that the study was conducted in a hospital setting where only patients with severe disease tend to get admitted. Similar findings were reported in an Italian study by Caruso et al. (2020), in which more than half of hospitalized COVID-19 patients demonstrated high CT severity scores. Similar patterns have been documented in studies from India, where older age, the presence of comorbidities, and longer symptom duration have been consistently associated with higher CT severity scores.14 The strong association between age and disease severity may be related to age-associated immune dysregulation, impaired viral clearance, and increased prevalence of comorbidities, which collectively contribute to more pronounced radiological involvement.15

The pattern of distribution of biochemical markers, including serum ferritin, CRP, ESR, WBC, and D-dimer, is also consistent with existing research showing that these indicators of coagulopathy and inflammation are frequently high in severe cases. The results of this study, which showed that 62% of participants had elevated D-dimer levels and 80% had elevated CRP, align with global evidence, including the study by Wang et al., which reported a substantial correlation between elevated D-dimer levels and the degree of lung involvement on CT.15 Another noteworthy aspect of the study findings was the role of prior COVID-19 history. Patients with reinfection or a history of COVID-19 illness tended to exhibit higher CT severity scores, possibly reflecting residual pulmonary compromise, persistent inflammatory changes, or incomplete recovery of lung architecture following the initial infection. This remains a relatively underexplored area in the literature, and the present study contributes valuable insights to the emerging evidence regarding post-COVID lung vulnerability.13,15

The underlying pathophysiology of COVID-19 explains the relationship between clinical characteristics and chest CT severity scores. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes a variety of pathophysiological reactions that are frequently reflected in imaging. In severe cases, COVID-19 results in widespread inflammation and destruction of the alveoli, resulting in consolidation and ground-glass opacities that can be evident on CT scans.16 Vascular permeability, pulmonary oedema, and eventually fibrosis are the outcomes of a hyperinflammatory response marked by cytokine release, which causes this diffuse lung involvement.17 As a result, since inflammatory markers like CRP and ESR are suggestive of a systemic inflammatory response, patients with severe CT scores frequently exhibit elevated levels of these markers, as observed in this study.18 Immunosenescence, the progressive deterioration in immune function linked to aging, can make it more difficult for elderly individuals to develop a strong defence against viral infections. A prolonged and uncontrolled inflammatory phase brought on by this compromised immune response may worsen lung injury and raise CT severity scores.19 Furthermore, comorbid conditions like diabetes and hypertension (linked to elevated ACE-2 receptor expression), which are linked to endothelial dysfunction and a pro-inflammatory state, are frequently found in older persons, further complicating the disease progression.20

One of the strengths of this study was the relatively large sample size, which enhanced the validity of the observed associations. Furthermore, by concentrating on a particular community in North Eastern India, the study offers insightful regional information that advances our knowledge of COVID-19. Despite its strengths, this study has a few limitations. The descriptive study design makes it difficult to establish causality. Furthermore, because of the unique demographics of North Eastern India, the study's findings may not be fully applicable to other regions or communities.

Conclusion

In summary, this study established a strong relationship between chest CT severity scores and determinants such as age, comorbidities, symptom duration, and prior COVID-19 history. These findings are consistent with existent literature, indicating that the chest CT severity score is a valid indicator of COVID-19 severity. Accordingly, the use of chest CT severity scoring may facilitate the early identification of high-risk patients, enabling clinicians to initiate timely and appropriate management.

Conflict of Interest

Nil

Supporting File

References

1. Rajaa S, Govindhan D, Thulasingam M. Profes-sional quality of life among physicians posted in COVID-19 clinics at a tertiary care hospital in South India: A cross-sectional analytical study. Int J Community Med Public Health 2023;10 (3):1207-13.

2. Pfortmueller CA, Spinetti T, Urman RD, et al. COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (CARDS): Current knowledge on pathophysiology and ICU treatment - A narrative review. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2021;35 (3):351-368.

3. Keni R, Alexander A, Nayak PG, et al. COVID-19: Emergence, spread, possible treatments, and global burden. Front Public Health 2020;8:216.

4. COVID19 India. COVID-19 Tracker | India [Internet]. [cited 2024 April]. Available from: https://www.covid19india.org

5. Sharma S, Aggarwal A, Sharma RK, et al., Correlation of chest CT severity score with clinical parameters in COVID-19 pulmonary disease in a tertiary care hospital in Delhi during the pandemic period. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 2022;53(1):166.

6. Thulasingam M, Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, et al. Contact tracing for COVID-19 in a healthcare institution: Our experience and lessons learned. Int J Health Allied Sci 2023;12(4):3.

7. Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, et al. CT imaging features of 2019 novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Radiology 2020;295(1):202-207.

8. Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A report of 1014 cases. Radiology 2020;296(2):E32-E40.

9. Bhandari S, Rankawat G, Bagarhatta M, et al. Clinico-radiological evaluation and correlation of CT chest images with progress of disease in COVID-19 patients. J Assoc Physicians India 2020;68(7):34-42.

10. Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, et al. Time course of lung changes at chest CT during recovery from Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Radiology 2020;295(3):715-721.

11. Francone M, Iafrate F, Masci GM, et al. Chest CT score in COVID-19 patients: correlation with disease severity and short-term prognosis. Eur Radiol 2020;30(12):6808-6817.

12. Shang J, Wang Q, Zhang H, et al. The relationship between diabetes mellitus and COVID-19 prognosis: A retrospective cohort study in Wuhan, China. Am J Med 2021;134(1):e6-e14.

13. Xu PP, Tian RH, Luo S, et al. Risk factors for adverse clinical outcomes with COVID-19 in China: a multicenter, retrospective, observational study. Theranostics 2020;10(14):6372-6383.

14. Caruso D, Zerunian M, Polici M, et al. Chest CT features of COVID-19 in Rome, Italy. Radiology 2020;296(2):E79-E85.

15. Wang L, Yang L, Bai L, et al. Association between D-dimer level and chest CT severity score in patients with SARS-COV-2 pneumonia. Sci Rep 2021;11(1):11636.

16. Osuchowski MF, Winkler MS, Skirecki T, et al. The COVID-19 puzzle: deciphering pathophysiology and phenotypes of a new disease entity. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9(6):622-642.

17. Savin IA, Zenkova MA, Sen'kova AV. Pulmonary fibrosis as a result of acute lung inflammation: molecular mechanisms, relevant in vivo models, prognostic and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23(23):14959.

18. Kalaiselvan P, Yingchoncharoen P, Thongpiya J, et al. COVID-19 Infections and inflammatory markers in patients hospitalized during the first year of the pandemic. J Prim Care Community Health 2023;14:21501319231206911.

19. Oh SJ, Lee JK, Shin OS. Aging and the immune system: The impact of immunosenescence on viral infection, immunity and vaccine immunogenicity. Immune Netw 2019;19(6):e37.

20. Tanzadehpanah H, Lotfian E, Avan A, et al. Role of SARS-COV-2 and ACE2 in the pathophysiology of peripheral vascular diseases. Biomed Pharmacother 2023;166:115321.