RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Department of Community Medicine, ESIC Medical College, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India

2Department of Community Medicine, ESIC Medical College, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India

3Department of Community Medicine, ESIC Medical College, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India

4Mr. Shrinivas Reddy, Department of Community Medicine, ESIC Medical College, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India.

*Corresponding Author:

Mr. Shrinivas Reddy, Department of Community Medicine, ESIC Medical College, Kalaburagi, Karnataka, India., Email: reddymrmcg@gmail.com

Abstract

Background & Objectives: The geriatric population is increasing globally and in India, raising concern as ageing is associated with multiple morbid conditions. Appropriate health-seeking behaviour is essential for managing these conditions. The elderly population residing in rural areas are particularly vulnerable. Hence, this study was conducted to determine the morbidity pattern and health-seeking behaviour among the geriatric population in a rural area.

Methods: This was a community-based cross-sectional study conducted among the elderly population residing in a rural area of Kalaburagi, Karnataka. A pre-tested, semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect data. Statistical analysis included frequency, percentage, and Chi-square tests to assess associations.

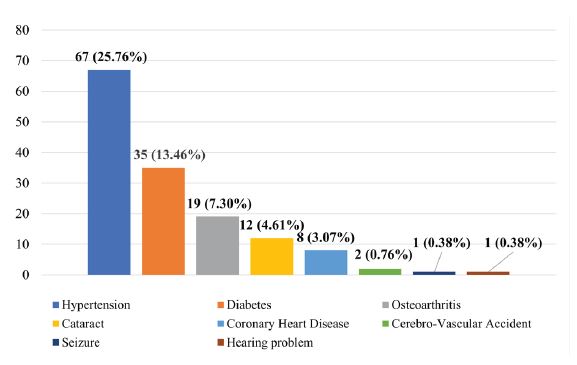

Results: Among the 260 participants, more than one-fourth (39.23%) had morbidity, with hypertension (25.687%) and diabetes (13.46%) being the most common conditions. Health-seeking behaviour was good (99.60%), with most participants availing services from government health facilities (55.38%).

Conclusion: The primary healthcare system needs to be strengthened to effectively manage common morbidities and improve the quality of life of the elderly. Government health facilities in rural areas should be further improved, with particular emphasis on geriatric programmes, so that the health-seeking behaviour observed among the geriatric population is maintained.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Ageing is a natural and inevitable biological process resulting from the accumulation of molecular and cellular damage over time, leading to a decline in physical and mental capacity and an increased risk of morbidity and mortality.1,2

According to the Government of India’s National Policy on Older Persons, a “senior citizen” or “elderly” individual is defined as someone 60 years of age or above. Those aged 60 -74 years are classified as the ‘young old’, those aged 75-84 years as the ‘middle old’, and those aged 85 years and above as the ‘oldest old’ or ‘infirm’.3,4

Globally, according to the World Population Prospects 2022, by 2050, one in six people worldwide will be over the age of 65, compared with one in eleven in 2019.5,6

In India, although the proportion of older persons in the total population is lower than that of many developed countries, the absolute number of older adults remains substantial. In 2021, 10.1% of the population was aged 60 years and above.7

According to the United Nations Population Fund’s India Ageing Report 2023, the population aged 60 years and above is projected to double from 10.5% (14.9 crore as of July 1, 2022) to 20.8% (34.7 crore) by 2050.8

India has the second largest aged population in the world. Statistical reports indicate that 80% of India’s elderly live in rural areas, placing them among the more vulnerable population groups.7,9

In Karnataka, the proportion of the elderly population was 11.5% in 2021 and is projected to rise to 15% by 2031.10

The burden of chronic disease in India is high, with high rates of morbidity and mortality, especially among the elderly. Specific chronic conditions such as degenerative diseases of the heart and blood vessels, cancer, accidents, diabetes, diseases of the locomotor system, respiratory illnesses, genitourinary conditions, and psychological problems are more common in older adults than in younger individuals.1,2,4

Health-seeking behaviour of the elderly is a predictor of their access to health care and is defined as the series of remedial actions undertaken to address perceived ill-health, and is influenced by a variety of factors.11 Therefore, understanding the morbidity pattern of older adults and the determinants of their health-seeking behaviour is essential.12 Hence, this study aimed to assess the morbidity pattern and health-seeking behaviour of the geriatric population in order to improve their health status and overall quality of life.

Materials & Methods

Study Area

The present study was conducted in a rural field practice area of the Department of Community Medicine, ESIC Medical College, Kalaburagi, located 25 km from Kalaburagi.

Study Design

Community-based cross-sectional study.

Study Period

The study was conducted over a period of two years, from June 2022 to June 2024.

Study Participants

All elderly individuals aged ≥60 years residing in Korwar were included in the study.

Sample Size Calculation and Sampling Procedure

The sample size was calculated using the formula, Z2 PQ/ e2. In this formula, Z represents the confidence interval (99%), P indicates prevalence, Q is formulated as (100- P), and d denotes allowable error (5%). According to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, the proportion of the geriatric population in 2021 was 10.1%.7 The population of the Rural Health training centre (RHTC) area, Korwar, is 2888.

Prevalence (P) = 10.1%, Q=100-10.1 = 89.9, Z value = 2.576 at 99%, d=5%

The sample size was calculated as:

n = (2.576)2× (10.1%) × (89.9)/ (5)2 = 241, which was rounded off to 260.

Considering the prevalence of the geriatric population, the calculated sample size was 241, rounded to 260. A house-to-house survey was conducted until the required sample size was achieved.

Inclusion Criteria

Elderly persons aged 60 years or above residing in the rural field practice area.

Elderly persons who are permanent residents of the rural field practice area.

Elderly persons who are willing to participate in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Elderly persons who are unable to cooperate for the study.

Data Collection Method

For data collection, each elderly participant was explained about the purpose of the study, and informed consent was obtained with assurance of confidentiality. After obtaining consent, a face-face interview was conducted to collect information on sociodemographic characteristics, morbidity patterns, and health-seeking behaviour.

Data Collection Tool

A pre-designed, pretested, semi-structured questionnaire was used for data collection. The questionnaire was administered by the interviewer.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, and analysed for frequency and percentage. The Chi-square test was applied as a test of significance, with a P-value of <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance and approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee, ESIC Medical College, Kalaburagi (No: ESICMC/GLB/IEC/48/2022; Dated: 10.06.2022).

Results

Majority of the study participants were in the 60–74 years age group (86.15%), with only 3.07% aged 85 years or above, indicating that the younger elderly group (60-74 years) constituted most of the sample. Gender distribution was nearly equal, with males (50.76%) slightly outnumbering females (49.24%).

A large proportion of the participants were unemployed (71.16%). Furthermore, illiteracy was found to be high (80.39%).

Most participants were married (82.69%), while 17.31% were widowed. In terms of socioeconomic status, nearly half of the participants belonged to Class V (46.15%), whereas only 1.15% were in Class I.

Regarding family structure, the majority of participants lived in joint families (57.70%). In terms of habits, 33.07% reported tobacco use, while 58.48% reported no addiction (Table 1).

Main Inference: The study population consisted predominantly of young elderly, unemployed, and illiterate individuals, with a high proportion belonging to lower socioeconomic classes and residing in joint families.

Out of the 260 participants, 39.23% had at least one morbidity, while 60.77% were morbidity-free. Among those with morbidity, 21.92% had a single morbidity, whereas 17.31% experienced multi-morbidity (Table 2).

The most common morbidity reported was hypertension (25.76%), followed by diabetes (13.46%), and osteoarthritis (7.30%). Other notable conditions included cataract (4.61%), coronary heart disease (3.07%), seizures (0.76%), cerebrovascular accidents (0.38%), and hearing problems (0.38%) (Figure 1).

Main Inference: Nearly two-fifths of the elderly population reported at least one morbidity, with hypertension and diabetes accounting for the majority of the reported conditions.

Analysis of the association between morbidities and sociodemographic variables revealed several significant relationships. Occupation showed a highly significant association (P <0.00001), with unemployed elderly individuals experiencing a greater burden of morbidity compared to those who were employed. Education was another important determinant, as illiterate participants had significantly higher morbidity than literates (P=0.01). Type of family also demonstrated a significant association (P=0.001), with participants living in joint families reporting more morbidities than those in nuclear families. Similarly, socioeconomic status was significantly related to morbidity (P=0.01), with a higher prevalence observed among individuals belonging to lower socioeconomic classes. No significant associations were observed with age, sex, marital status, habits, or geriatric depression (Table 3).

Main Inference: Sociodemographic variables such as education, occupation, family type, and socioeconomic status play a crucial role in determining the morbidity burden among the elderly.

Among the study participants, the majority preferred government hospitals (55.38%). The reasons cited for choosing a particular health facility included good treatment (56.53%), easy access (56.15%), low or no cost of care (27.69%), availability of emergency services (26.53%), and other factors (17.30%). Majority of the study participants (65.38%) reported having a health facility located within 5 km of their residence (Table 4).

Main Inference: Health-seeking behaviour among the participants was excellent, with almost all participants seeking care when needed. A majority preferred government health facilities, primarily due to their accessibility, affordability, and perceived quality of treatment.

Discussion

Sociodemographic Details

In the present study, the majority of the participants (86.15%) belonged to the 60-74 year age group, which is consistent with findings from studies conducted by Kalpana MK et al., (89.54%), Patnaik A et al., (73%), and others.13,14,4,15,16 This could be attributed to improving public health conditions in rural areas.

The gender distribution in our study showed nearly equal representation of males (50.76%) and females (49.24%), similar to the study by Poudel M et al.,(male - 50.9%, female - 49.1%). However, a higher proportion of female participants was reported in studies by Kalpana MK et al., (52.27%), Patil SK et al., (60%), and several others.11,7,13,18,11,16,19-23 Conversely, some studies reported a higher proportion of male participants, such as Bahran S et al.,(54.98%), Ahamed et al., (52.1%), and Hossain et al., (52.5%).24,15,21

In the present study, 80.39% of participants were illiterates, which is slightly lower than the proportion reported by Kumar et al., (88.12%), but higher than that observed in studies by Patil SK et al.,(4%), Kalpana MK et al., (30%), and various other studies.25,18,13,15,16,20,23,26 Such variations could be due to geographical and sociodemographic differences across study settings.

In this study, the majority of participants were unemployed (71.16%), although this proportion was lower than those reported by Palepu S et al.,(97.2%), Kumar et al., (75.62%), Gupta et al., (80%), and Nandini et al.,(95.7%).25,19,14,15Conversely, in several other studies,unemployment rates among the elderly were lower than the current study.14,15,28 These differences may be explained by advancing age, dependence on family support, or limited employment opportunities in rural areas.

Most participants in the current study were married (82.69%), while 17.31% were widowed. This finding is consistent with studies conducted by Kalpana MK et al.,(92%), Bahran S et al., (70.1%), Ahamed et al., (71.8%) and several others.13,24,15,28,21,22 In contrast, a study conducted by Aye et al.,reported a higher proportion of widowed participants (51.8%).28

Among the 260 participants, the largest proportion (46.15%) belonged to Class V (lower socioeconomic status), which is comparable to findings from studies conducted by Palepu et al., (52.4%), Poudel M et al.,(56%), Sarkar et al.,(37.4%).27,17,29,12,25 However, studies by Barua et al.,(57.6%) and Kumar et al., (56.87%) reported a majority belonging to Class III socioeconomic status.12,25 Studies by Ahmed et al., (81.1%), Nandini et al.,(47.14%) found most participants in Class I socioeconomic status.15,16 These differences likely stem from variations in study settings, particularly the limited access to education and employment opportunities commonly observed in rural areas.

In the present study, majority (57.70%) of the study participants belonged to joint families, which is consistent with the findings reported by Palepu S et al., (70.4%), and Prabhakar T et al.,(71.42%).27,22 This may be attributed to the fact that joint family structures are more common in rural parts of India.

The current study showed that majority (58.48%) of the study participants reported no addictive habits. Tobacco use, either in smoking or smokeless form, was observed in 33.07%, while alcohol consumption was noted in 2.30%. These figures are lower than those reported by Kumar et al., [alcohol (15%)], and Aye et al., [tobacco (40%), alcohol (6%)]. 25,28 Such variations likely arise due to differences in geographic locations.

Morbidity Pattern

In this study, morbidity was observed in 39.23% of participants, which is comparatively lower than the findings of Kumar et al., (76.9%), and Gnanasabai et al.,(64.9%).25,23 This could be because rural populations tend to be more physically active, which helps reduce various health risk factors.

Among those with morbidity, most participants (21.92%) had a single morbidity, which is similar to the findings reported by Poudel M et al., (30.9%), and Aye et al., (26%). 17,28 In the current study, 17.31% of participants had multimorbidity, comparable to the results of Poudel M et al.,(17.4%).17 However, this proportion contrasts with the higher prevalence reported by Aye et al.,(26%), Yogesh et al.,(62.5%).28,30 These variations could be attributed to diversity in the quality of health care across different study settings.

The most prevalent morbidity in the present study was hypertension (25.76%), followed by diabetes mellitus (13.46%). This pattern aligns with findings of Kalpana MK et al., [hypertension (49.39%), diabetes mellitus (43.33%)] and several other studies.13,21,23 In contrast, different morbidity profiles were reported in other research: Barua et al., identified acid peptic disease (70.4%) and cataract (58.4%) as the most common conditions; Gupta et al., found musculoskeletal problems (57.3%) followed by eye disorders (54%); and Kumar et al.,reported nonspecific generalized weakness (55.1%) and gastrointestinal problems (47.2%) as the most prevalent.12,19,25 At the national level, the most prevalent morbidity was cardiovascular diseases (34.6%), followed by hypertension (25.8%), diabetes mellitus (23.2%), heart disease (1.8%), and stroke (1.8%).4

The present study assessed depression using the Geriatric Depression Scale - 4, and found that 3.85% of the study participants were depressed. This prevalence was much lower than that reported by Patnaik et al.,(59.5%) and was comparable to the findings of Poudel M et al., (4.4%).14,17 The lower prevalence in the current study may be due to the stronger family and community social support in the study setting.

In the current study, a statistically significant association was observed between morbidity and factors such as education, occupation, socioeconomic status, and type of family. Similar to our findings, Gupta et al., also reported a statistically significant association between morbidity and education.19

This association may be explained by the fact that literate individuals are more likely to be aware of their morbid conditions, while individuals belonging to higher socioeconomic groups, the unemployed, and those living in joint families may experience increased stress levels, which could contribute to the development of morbidity.

Health-Seeking Behaviour

In the present study, most participants (55.38%) preferred government health facilities, which is similar to the findings of Prabhakar T et al., (51.6%). However, this contrasts with several other studies,where the majority preferred private healthcare services.22,4,13,26The preference for government facilities in the current study may be attributed to the close proximity of these centres and the nature of illness.

Regarding the reasons for choosing a particular health facility, the majority cited good quality of treatment (56.53%), easy access (56.15%), and low or no treatment cost (27.69%). Similar findings were reported by Ahmed et al.,where self-preference accounted for 65%, accessibility for 32.7%, and affordability for 6.8%. Nandini et al.,also found that proximity to home (25.7%), and affordability (17.1%) were key determinants.15,16

In terms of reasons for not seeking treatment, 0.40% of participants reported old age as the primary reason, which aligns with the findings of Nandini et al., (1.4%).16

Conclusion

In our study, one-fourth of the participants had chronic morbidities. The most common conditions identified were hypertension, diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, and cataract. The morbidity burden highlights the need for focused efforts to provide specialized medical care for the elderly so they can continue to participate actively in society.

Early detection and timely management of common geriatric conditions through regular screening, health check-ups, appropriate counselling, and consistent follow-up is essential to maintain their health, enhance quality of life, and prevent potential issues from the condition. Educating older adults, their families, and the wider community about the importance of self-care, blood pressure monitoring, and blood sugar control is also crucial. The primary health-care delivery system needs to be strengthened and equipped in order to facilitate community-level management of common morbidities. There is a pressing need to develop comprehensive geriatric health services that are easily accessible, inexpensive, and readily available at the community level. Priority should be given to the ageing population in health policies, and primary healthcare services should be strengthened with geriatric-specialized provisions capable of addressing common health issues among the elderly. More community-based studies, training, and research are needed in the fields of gerontology and geriatrics.

The majority of participants approached government facilities to seek health care, and the study concluded that their health-seeking behaviour was good. Thus, it is necessary to improve government facilities in rural areas, with particular attention to geriatric programmes. To facilitate this, policymakers need to give greater attention to rural elders. A more in-depth understanding of the various factors influencing healthcare-seeking behaviour can be obtained through qualitative research.

Financial Support (Funding agency if any)

Nil

Conflicts of interest

Nil

Approval of Institutional Ethical Committee

Approved (ESICMC/GLB/IEC/48/2022)

Acknowledgements

I extend my heartfelt thanks to all the study participants for their participation in the study. I am grateful to the medical officer, all PHC staff’s, people of Korwar for their valuable assistance throughout the study period.

Supporting File

References

1. Park K. Park’s textbook of preventive and social medicine. 26th ed. Jabalpur, India: M/s Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; 2021. p. 677.

2. World Health Organization. Ageing and health [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/ fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

3. Kadri AM, Kundapur R, Khan AM, et al. IAPSM’s Textbook of Community Medicine. Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2019. p. 767.

4. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), MoHFW. Longitudinal ageing study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017-18: India report. Mumbai: IIPS; 2020. Available from: https://www.iipsindia. ac.in/sites/default/files/LASI_India_Report_2020_ compressed.pdf&ved

5. United Nations. Ageing [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 2]. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/ageing

6. World Health Organization. Ageing [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www. who.int/health-topics/ageing#tab=tab_1

7. Government of India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, National Statistical Office. Elderly in India 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 10]. Available from: https://mospi.gov.in/web/ mospi/reports-publications

8. National Health Resource System Centre. Health Dossier 2021: Reflections on key health indicators – Karnataka [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 10]. Available from: https://nhrscindia.org.

9. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). India Ageing Report 2023 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2022 Jun 2]. Available from: https://india.unfpa.org/ caring for our elders

10. Nair LV. Elderly in India: A sociological analysis. Rajagiri Journal of Social Development 2012;4:6- 24.

11. MacKian S. A review of health seeking behavior: Problems and prospects. Manchester, UK: University of Manchester; 2002. p. 137-46.

12. Barua K, Borah M, Deka C, et al. Morbidity pattern and health-seeking behavior of elderly in urban slums: A cross-sectional study in Assam, India. J Family Med Prim Care 2017;6(2):345-50.

13. Kalpana MK, Nandkeshav AR, Harshawardhan MN. Assessment of morbidity profile and health-seeking behaviour of older adults in a rural field practice area of a tertiary health care centre of Western Maharashtra. Indian J Pub Health Res Development 2024;15(2):150-5.

14. Patnaik A, Mohanty S, Pradhan S, et al. Morbidity pattern and health‑seeking behavior among the elderly residing in slums of Eastern Odisha: A cross-sectional study. J Indian Acad Geriatr 2022;18(4):201‑7.

15. Ahamed F, Ghosh T, Kaur A, et al. Prevalence of chronic morbidities and healthcare seeking behavior among urban community dwelling elderly population residing in Kalyani Municipality area of West Bengal, India. J Family Med Prim Care 2021;10(11):41939.

16. Nandini C, Saranya R. A cross-sectional study on health seeking behaviour among elderly in Shimoga. Natl J Community Med 2019;10(12):645-8.

17. Poudel M, Ojha A, Thapa J, et al. Morbidities, health problems, health care seeking and utilization behaviour among elderly residing on urban areas of Eastern Nepal: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2022;17(9):1-16.

18. Patil SK, Pavithran S, Livingston LS. Morbidity pattern and health-Seeking behavior among elderly residing in the rural area of Palakkad district, South India. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 2024;15(1):132-8.

19. Gupta E, Thakur A, Dixit S. Morbidity pattern and health seeking behaviour of the geriatric population in a rural area of district Faridabad, Haryana: a cross-sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Health 2019;6(3):1096-101.

20. Thakan S, Mehta A, Singh R. A community based cross- sectional study on morbidity pattern of elderly in rural area of Jhalwar, Rajasthan. Asian J Pharm Res 2022;15(1):77-80.

21. Hossain SJ, Ferdousi MJ, Siddique MB, et al. Self-reported health problems, health care seeking behaviour and cost coping mechanism of older people: Implication for primary health care delivery in rural Bangladesh. J Family Med Prim Care 2019;8(3):1209-15.

22. Prabhakar T, Goel MK, Acharya AS. Healthseeking behavior and its determinants for different noncommunicable diseases in elderly. Indian J Community Med 2023;48(1):1616.

23. Gnanasabai G, Kumar M, Boovaragasamy C, et al. Health seeking behaviour of geriatric population in rural area of Puducherry- a community based cross sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Health 2020;7(9):3665-8.

24. Bahram S, Al Sayyad AS, Al Nooh F, et al. Morbidities and healthseeking behavior of elderly patients attending primary health care in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Saudi J Med Med Sci 2022;10(3):23642.

25. Kumar V, Mishra S, Srivastava A, et al. Morbidity pattern and health-seeking behavior among elderly population in rural area of district Barabanki: A cross-sectional study. Int J Med Sci Public Health 2020;9(5):294-299.

26. Akter, S, Azad T, Rahman MH, et al. Morbidity patterns and determinants of healthcare-seeking behavior among older women in selected rural areas of Bangladesh. Dr Sulaiman Al Habib Med J 2023;5:70-79.

27. Palepu S, Bandyopadhyay A, Nandan T, et al. Morbidity profile and healthcare service utilization pattern among geriatric population in the rural Himalayan Region of Uttarakhand, India: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2023;15(12):1-8.

28. Aye SKK, Hlaing HH, Htay SS, et al. Multimorbidity and health seeking behaviours among older people in Myanmar: A community survey. PLoS One 2019;14(7):1-15.

29. Sarkar A, Mohapatra I, Rout RN, et al. Morbidity pattern and healthcare seeking behavior among the elderly in an urban settlement of Bhubaneswar, Odisha. J Family Med Prim Care 2019;8(3):944-9.

30. Yogesh M, Makwana N, Trivedi N, et al. Multimorbidity, health Literacy, and quality of life among older adults in an urban slum in India: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2024;24:1833.