RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Jyoti Pradhan, Senior Resident, Department of Community Medicine and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

2Department of Community Medicine and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India

3Department of Community Medicine and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India

*Corresponding Author:

Jyoti Pradhan, Senior Resident, Department of Community Medicine and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India., Email: drpradhanjyoti@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: In the wake of the tobacco epidemic, awareness about the harmful effects of tobacco consumption among the population, especially in the urban slum areas of India, remains poor.

Aim: This community-based, cross-sectional analytical study in a metropolitan area of Central India aimed to evaluate tobacco awareness and consumption patterns and their relationships with sociodemographic characteristics and non-communicable disease outcomes among middle-aged and older adults.

Methods: A semi-structured interview schedule adapted from the WHO STEPS survey and the GATS survey (version 2) was used. The association between independent variables and tobacco awareness was tested using the chi-square test. Binomial logistic regression was used to fit the final model.

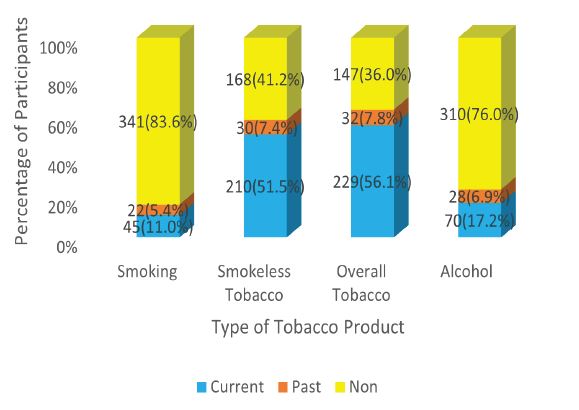

Results: Only half of the participants (57.1%) were aware of the harmful effects of tobacco. The majority of the participants (83.6%) were nonsmokers. The most common type of smoking product used was Bidis or Hand-rolled Cigarettes. Smokeless tobacco consumption, mainly Gudakhu, was found to be very high (51.5%), especially among women. Television was the most common source of information. A significant association was found between tobacco awareness and sociodemographic variables, smokeless tobacco and alcohol use, exercise, and hypertension using the Chi-square test. Finally, using multivariate binary logistic regression, it was found that older age [P=0.01], illiteracy [P=0.001], socioeconomic status [P=0.001], overcrowding [P=0.040], and lack of exercise [P=0.039] were significantly associated with low awareness.

Conclusion: Tobacco awareness was low among illiterate, unemployed populations belonging to the lower socioeconomic status and living in overcrowded conditions. Awareness was higher among tobacco users despite low quit rates.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Tobacco consumption has been significantly associated with increased mortality and morbidity.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) ’s global target is to reduce tobacco use by 30% by 2025.2 According to the National Family Health Survey 5 (NFHS 5) data of India, the prevalence of tobacco use in any form among women and men is 8.9% and 38% respectively.3 According to the Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2 (GATS), a significant portion of the adult population in Chhattisgarh, a state in Central India, uses tobacco.4 The NFHS 5 Chhattisgarh data shows that the percentage of women and men who used any tobacco was 17.3% and 43.1% respectively.5 This percentage was higher in urban areas than in rural areas. A study by Verma et al., found that the mean age of initiation for smoked tobacco and smokeless tobacco (SLT) in India increased between 2009-2010 to 2016- 2017.6 Despite many efforts and guidelines, awareness about the full spectrum of harmful effects of the usage of tobacco of all varieties remains poor, especially among women even if women are the highest users of smokeless tobacco in Central India.5

The use of tobacco has been linked to almost all types of noncommunicable diseases. Tobacco addiction can cause psychological and physical cravings with mental health disorders. Frequent users of tobacco often have lower immunity and are prone to infections.7

The literature review prior to the study revealed very few studies on tobacco awareness in Chhattisgarh, Central India. Most of the population, except health-related professionals, are not aware of the full range of harm from tobacco product use and thus tend to underestimate the impact of tobacco on their ill health. Hence, it is the need of the hour to increase awareness about the adverse effects of tobacco addiction.

Some Tobacco cessation and control guidelines are the COTPA Act, the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the MPOWER strategy, pictorial tobacco warnings guidelines, etc. The National Tobacco Control Program (NTCP), launched in 2007-08 by the Government of India, aims to reduce tobacco consumption, raise awareness, and enforce tobacco control laws under COTPA.8 By the 12th Five- Year Plan, NTCP was expanded to all 36 states/UTs, reaching 612 districts, and successfully reduced tobacco use by 8.1 million people.9 The National Program for Noncommunicable Diseases (NP-NCD) has also included screening for tobacco addiction and chronic respiratory diseases by frontline workers.

Materials and Methods

This was a community-based, cross-sectional study conducted in an urban area of Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India, in 2023-2024. The sample size was calculated using the formula Z2 P(1-P)/d2, where Z = 1.96 at a 5% level of significance and d is the absolute precision at 5%. The highest prevalence of tobacco use in Chhattisgarh was reported in NFHS 5 as 43.1%, and using this, the minimum sample size was 377.5. Data from 408 individuals were included in the study. The inclusion criteria were individuals aged 40-59 years (middle-aged) and ≥ 60 years (old age), residing in the area for more than 6 months. Individuals who were unavailable during the visits, too sick to interact, or with impaired comprehension were excluded from the study. The study was conducted in the urban field practice area (Zone 7) of a tertiary care hospital in Raipur, India. Data collection was done by house-to-house visits in the community. Households were selected using simple random sampling. Various methods, like rotating bottles to choose a street and lottery methods to select participants, were used. Only one participant was taken from each house.

Operational definitions were evaluated before the start of the study, including cut-off criteria for diabetes (WHO guidelines), hypertension (JNC 8), waist to hip ratio, body mass index, etc. Overcrowding was assessed using the person per room and room area criteria. All smokers smoking during the study period and all those who had quit smoking less than one year before the assessment were considered current smokers.11 Similar definitions were used for smokeless tobacco users.

A semi-structured questionnaire, adapted from the WHO STEPS survey and the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) version 2, was used in the study. Questions on passive smoking exposure were also included. The questionnaire was pilot tested in the Amanaka area of Raipur, India, to identify and correct errors. Details were collected on the sociodemographic profile, addiction history, history of chronic diseases, treatment history, anthropometry measurements, etc. Tools used were inextensible measuring tapes, a digital weighing machine, an Omron Glucometer, a stadiometer, a digital sphyg-momanometer, etc. A portable glucometer measured random blood glucose levels to detect Type II diabetes in those with no prior history. 12,13

Statistical Analysis

Data was compiled in Excel sheets and analyzed using IBM SPSS software version 27. All the categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The continuous variables were summarized using various measures of central tendency, such as the mean, median, mode, standard deviation, and interquartile range. Initially, the chi-square test of significance was used to test the association between tobacco awareness and other independent variables. Independent Sample T test and One-Way ANOVA test were applied to find out the mean and SD of continuous variables. Any P value < 0.05 was taken as significant, and <0.001 was taken as highly significant. After ruling out multicollinearity (via Pearson's Correlation test) and applying goodness of fit tests, the significant variables from the Chi-square test were included in a binary logistic regression analysis to estimate crude odds ratio (OR) and adjusted odds ratio (AOR).

Results

Tobacco Consumption Patterns Among the Study Participants

Smoking

The prevalence was high among males, with 24.2% currently smoking. A significant association was present between gender and smoking status (P value <0.05) (Figure 1).

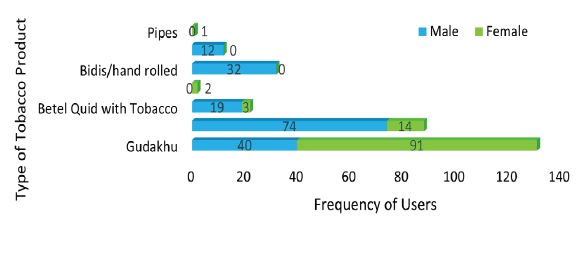

Among the smokers, most of the participants smoked one type of smoking product, preferably. The most common type of smoking product, preferably. The most common type of smoking product used was Bidis or Hand-rolled Cigarettes (Figure 2).

Out of the 45 smokers, 12 used ≤2, 14 used 3 to 4, and 19 used ≥5 cigarettes/bidis per day. The mean years of smoking among them was 27.8 ± 1.727 years.

Smokeless Tobacco

Many of the participants used multiple smokeless tobacco products. 58.8% of males and 45.6 % of females were habitual smokeless tobacco users. A significant association was found between gender and smokeless tobacco consumption, with a P-value <0.05. Gudakhu was the most commonly used smokeless tobacco product, especially among women (40.3%).

About 67.2% of current tobacco users and 68.8% of past tobacco users were literate. Most current and former tobacco users belonged to the upper, lower, and lower-middle SES groups. About 26 participants used both smoking and smokeless tobacco products. Using the Chi-Square test, a significant association was found between age, gender, education, and SES and overall tobacco consumption.

Among 182 males, 69.3% consumed tobacco in some form. 10.4% of males are past users, and 20.3% did not use tobacco in any form, smoking or non-smoking. Among 226 female participants, 45.6% were current tobacco users and 5.8% were past users.

Passive Smoking

In this study, passive smoking was assessed using a Likert Scale of exposure from daily, weekly, monthly, to less than monthly (equivalent to no exposure), adapted from the GATS (Global Adult Tobacco Survey 2020) questionnaire.

About one third of the participants (34.3%) reported having been exposed to passive smoking. Among 182 males, 86 (47.3%) were exposed to passive smoking, and among 226 females, 54 (23.9%) were exposed. About 27.9% of participants had daily exposure to passive smoking.

Tobacco and Alcohol Co-use

The prevalence of alcohol consumption was 17.1% in the study population. Overall, tobacco consumption was found in 58 (82.9%) of the 70 current alcoholics. Among the 310 non-alcohol users, 149 (48.1%) were current tobacco users. Furthermore, among the 28 past alcohol users, 22 (78.6%) were also using tobacco. The mean quantity of alcohol consumption was 149.43 ± 66.8 ml per session of drinking, with a range of 240 ml.

Overall, tobacco consumption had a significant association with alcohol consumption (P value <0.05).

Tobacco Awareness Among the Study Participants

Among the 408 people interviewed about tobacco awareness, 248 responded yes. However, when asked to elaborate on the harmful effects of tobacco, only 233 (57.1%) people could give correct responses and were included in the “ Aware’’ group. The rest 15 out of the 248 either could not answer the following question or gave incorrect responses. Some of the incorrect responses were malaria, dengue, leprosy, etc.

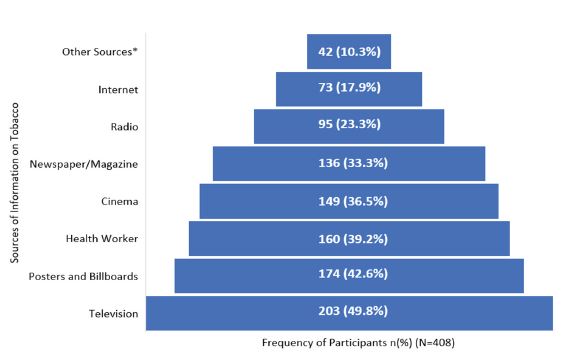

Sources of Tobacco Awareness

Participants were asked about various sources of information on tobacco awareness. It was a multiple choice question (Figure 3).

*The “other sources’’ of information were school/ education (15, 3.7%), friend, relative, or family member with cancer history (11,2.7%), rally (7, 1.7%), cigarette packets (5, 1.2%), quack (2, 0.5%), and religious sermons (2, 0.5%).

Responses to Harmful Effects of Tobacco Question

Among the 233 participants in the Tobacco Aware group, cancer emerged as the most recognized harmful effect, reported by 215 participants (92.3%), including specific mentions of oral, lung, and head-and-neck cancers. Lung-related conditions were the next most common, with 73 participants (31.35%) citing diseases such as TB, asthma, or COPD. Other reported effects included dental problems (6.9%), mouth odor (3.0%), mouth ulcers or cheek swelling (4.7%), infertility (3.4%), PCOS/acne (1.3%), addiction (4.3%), heart diseases (4.3%), stroke or paralysis (2.1%), myalgia or fatigue (1.7%), reduced longevity (1.7%), and burning feet (0.4%).

Table 2 demonstrate the association of tobacco awareness with different variables using regression analysis.

Variables that were significant in Table 1 were tested for multicollinearity and subsequently entered into a binary logistic regression model. After applying Goodness-of- Fit tests, all variables were analyzed together in Model 2, adjusted for covariates. Age, education, socioeconomic status (SES), overcrowding, and exercise remained significantly associated with tobacco awareness (P < 0.05). Older participants showed lower awareness (AOR 0.427, 95% CI 0.224-0.815, P = 0.01). Literate individuals were more aware than illiterate individuals (AOR 0.363, 95% CI 0.195-0.677, P = 0.001). Participants from higher SES had greater awareness (AOR 3.868, 95% CI 1.727-8.662, P = 0.001). Those living in overcrowded conditions were less aware (AOR 0.579, 95% CI 0.302- 0.969, P = 0.040). Individuals who exercised regularly also demonstrated higher awareness (AOR 0.541, 95% CI 0.302-0.969, P = 0.039). No significant association was observed between hypertension and tobacco awareness in the adjusted model.(Table 2)

Discussion

In a study by Rupani et al., in India in Bhavnagar’s urban slum, 27.3% of individuals used smokeless tobacco (SLT), with addiction being the primary barrier to quitting.14 A cross-sectional study by More et al., in Mangalore found that awareness was high about oral cancer, tooth staining, and dental implants, but there were gaps in knowledge about gum disease and wound healing.15 This is similar to the current study, where only 57% participants were aware of the harmful effects of tobacco. Lakra et al., found that oral cancer patients in north India were unaware of early signs of oral cancer, with many continuing tobacco use.16 The majority came from lower SES backgrounds; thus, there is a need for improved education on prevention. In Kapoor et al., after training security guards, awareness of tobacco laws increased from 20% to over 80%.17 Two-thirds of participants were aware of COTPA Section 4, and 33.6% of tobacco users and 58.4% of observers knew about Section 6b. Raman et al., in South Chennai, found that 33.2% of respondents did not change their behavior after viewing tobacco warning ads.18 Additionally, 90.3% of participants were unaware of professional help for quitting.

Subasinghe et al., conducted a hospital based study in Sri Lanka. They found that tobacco consumers are more likely to be aware of the harmful effects of tobacco use than non consumers (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.45-2.74).19 The Swatan et al. study on tobacco smoking addiction in rural Indonesian communities identified key determinants such as peer influence, lack of awareness about health risks, and cultural norms that encourage smoking.20 This is similar to the findings of the current study.

In our study, the majority of respondents knew about cancer as an adverse effect, but knowledge about the harmful effects of tobacco on other organs was poor. A 2022 survey in Poland by Szymanski et al., found high awareness of tobacco-related diseases.21 In the study by Ranney et al., in June-July 2021, on U.S. adults, awareness of health risks from alcohol and tobacco couse ranged from moderate (e.g., throat cancer at 65.4%) to low (e.g., colorectal cancer at 23.1%).22 King et al., in Australia found that while most participants recognized smoking’s risks, only a quarter accurately quantified the mortality risk.23 Public support for local tobacco policies is essential. Brief, tailored messaging can shape public understanding of nicotine-related risks and encourage healthier behaviors as shown in Rhoades et al., Villanti et al. and Peterson et al. 24-26 Agaku and Filippidis’s study found that 24.4% of school personnel across 29 African countries were unaware of the health consequences of tobacco use.27 Low education and lack of tobacco control training were significantly associated with unawareness, similar to the current study.

Strengths

The study was conducted in urban slum areas, thus focusing on increasing awareness through community interventions.

Limitations

Temporal association can not be established in a cross-sectional study. We considered only the urban population; hence, the rural population might differ on the variables.

Conclusion

Tobacco awareness was found to be low among illiterate and unemployed individuals, particularly those belonging to lower socioeconomic strata and residing in overcrowded conditions. Despite this, awareness was paradoxically higher among tobacco users themselves, although quit rates remained low. Illiteracy and easy accessibility of tobacco products at low prices, especially for smokeless tobacco and a lack of awareness have led to extensive consumption of these products; hence, efforts must be made in these directions by various measures, such as policies, bans, taxes, and health education.

Some recommendations based on the results of the study are:

• Tobacco Awareness integration into regular visits by health providers at any level.

• Risk-factor counseling integration with existing program delivery at all levels of care.

• Training of healthcare workers.

• More focus on lower education, the low-income population living in underserved areas.

Funding

The study had no funding sources, grants, or external support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting File

References

1. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2023: protect people from tobacco smoke. [cited 2025 Feb 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/ publications/i/item/9789240077164

2. World Health Organization. Tobacco use: achieving the global target of 30% reduction by 2025. East Mediterr Health J 2015;21(12);934-936.

3. NFHS-5_INDIA_REPORT.pdf. [cited 2023 Feb 27]. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS- 5Reports/NFHS-5_INDIA_REPORT.pdf

4. Global Adult Tobacco Survey. [cited 2024 Jan 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/ noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-adult-tobacco-survey

5. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) 2019-21: Chhattisgarh. 2021 [cited 2023 Feb 27]. Available from:https://ruralindiaonline.org/or/library/ resource/national-family-health-survey-nfhs-5- 2019-21-chhattisgarh/

6. Verma M, Rana K, Bhatt G, et al. Trends and deter-minants of tobacco use initiation in India: analysis of two rounds of the Global Adult Tobacco Survey. BMJ Open. 2023;13(9):e074389.

7. Smoking. [cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from:https:// my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/17488- smoking

8. National Tobacco Control Programme (NTCP) :: National Health Mission. [cited 2025 Feb 16]. Availablefrom:https://nhm.gov.in/index1. php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=1052&lid=607

9. National Tobacco Control Programme (NTCP) | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | GOI. [cited 2025 Feb 16]. Available from: https://mohfw.gov. in/?q=major-programmes/other-national-health-programmes/national-tobacco-control-programme-ntcp

10. Physical Status: The use and interpretation of Anthropometry.pdf [cited 2022 Jan 18]. Availa

blefrom:https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/37003/WHO_TRS_854.pdf?sequence=1

11. Organización Mundial de la Salud. HEARTS WHO risk prediction chart 2020. Ginebra: Organización Mundial de la Salud; 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 7]. Availablefrom: https://apps.who.int/iris/ handle/10665/351150

12. Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance, Monitoring and Reporting [cited 2025 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunica-ble-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/steps

13. GATS Questionnaire [cited 2025 Feb 16]. Availablefrom:https://www.who.int/teams/ noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-adult-tobacco-survey/questionnaire

14. Rupani MP, Parikh KD, Kakadia MJ et al. Cross sectional study on smokeless tobacco use, awareness and expenditure in an urban slum of Bhavnagar, western India. Natl Med J India 2019;32 (3):137-140.

15. More AB, Rodrigues A, Sadhu BJ. Effects of smoking on oral health: Awareness among dental patients and their attitude towards its cessation. Indian J Dent Res 2021;32(1):23-26.

16. Lakra S, Kaur G, Mehta A et al. Knowledge and awareness of oral cancer patients regarding its etiology, prevention, and treatment. Indian J Dent Res 2020;31(4):625-628.

17. Kapoor S, Mohanty VR, Balappanavar AY et al., Feasibility of the novel 'Tobacco-Free Hospital' model and its compliance assessment at a tertiary care hospital of New Delhi, India. J Educ Health Promot 2022;11:382.

18. Raman P, Pitty R. Tobacco Awareness with Socio-economic Status and Pictorial Warning in Tobacco Cessation: An Exploratory Institutional Survey in a Semi-urban Population. J Contemp Dent Pract 2020;21(10):1122-1129.

19. Subasinghe SPKJ, Hettiarachchi PVKS, Jayasinghe RD. Prevalence, Habit Pattern, and Awareness on Harmful Effects of Tobacco/Areca Nut Use among Patients Visiting a Tertiary Care Center in Sri Lanka. South Asian J Cancer 2023;13(1):4-9.

20. Swatan JP, Sulistiawati S, Karimah A. Determinants of Tobacco Smoking Addiction in Rural Indonesian Communities. J Environ Public Health 2020;2020:7654360.

21. Szymański J, Ostrowska A, Pinkas J et al.Awareness of Tobacco-Related Diseases among Adults in Poland: A 2022 Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19(9):5702.

22. Ranney LM, Kowitt SD, Jarman KL et al., Messages About Tobacco and Alcohol Co-Users. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2025;86(1):140-148.

23. King B, Borland R, Yong HH et al., Understandings of the component causes of harm from cig-arette smoking in Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev 2019;38(7):807-817.

24. Rhoades RR, Beebe LA, Mushtaq N. Support for Local Tobacco Policy in a Preemptive State. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16(18):3378.

25. Villanti AC, West JC, Mays D et al., Impact of Brief Nicotine Messaging on Nicotine-Related Beliefs in a U.S. Sample. Am J Prev Med 2019;57(4):e135-e142.

26. Petersen AB, Thompson LM, Dadi GB et al., An exploratory study of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs related to tobacco use and secondhand smoke among women in Aleta Wondo, Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health 2018;18(1):154.

27. Agaku IT, Filippidis FT. Prevalence, determinants and impact of unawareness about the health consequences of tobacco use among 17,929 school personnel in 29 African countries. BMJ Open 2014;4(8):e005837.