RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Dr. Sowjanya D, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Community Medicine, Shridevi Institute of Medical Sciences & Research Hospital, Tumkur, Karnataka, India.

2Department of Community Medicine, Shridevi Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Hospital, Tumkur, Karnataka, India

3Department of Community Medicine, Shridevi Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Hospital, Tumkur , Karnataka, India

4Department of Forensic Medicine, Shridevi Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Hospital, Tumkur, Karnataka, India

5Department of Community Medicine, Shridevi Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Hospital, Tumkur, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Sowjanya D, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Community Medicine, Shridevi Institute of Medical Sciences & Research Hospital, Tumkur, Karnataka, India., Email: sowjanyad6@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Home-Based Newborn Care (HBNC) is a strategy implemented by the Government of India since 2011 to address the issue of newborn deaths in the first week of life. It ensures a continuum of care for newborns and postnatal mothers, addressing the burden of neonatal mortality, which stands at 25.7 per 1000 live births in India.

Aims/Objectives: To estimate the knowledge regarding HBNC among Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and ASHA facilitators, and to compare the knowledge of HBNC across different domains between ASHAs and ASHA facilitators.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted using a multi-stage random sampling technique. A total of 584 ASHA workers and ASHA facilitators from one district, who had previously undergone training in HBNC and were attending Home-Based Care for Young Child training at the district training centre, were included in the study. A validated and pre-tested questionnaire was used for data collection. The total knowledge score was categorized as good, average, and poor. Knowledge related to maternal care and essential newborn care within the HBNC programme was assessed and compared between ASHAs and ASHA facilitators.

Results: Of the 584 community health workers included in the study (510 ASHAs and 74 ASHA facilitators), the majority of facilitators (67.5%) and ASHAs (62.94%) belonged to the middle age group (36-45 years). A significantly higher proportion of facilitators had higher education than ASHAs and possessed more than 10 years of work experience (87.84%). HBNC knowledge was significantly better among facilitators, with 46% achieving good scores compared to 25.9% of ASHAs. Similarly, a greater proportion of facilitators demonstrated good knowledge in maternal care (62.16%) relative to ASHAs (41.17%). Although both groups performed better in essential newborn care, mean score comparisons revealed significant differences favouring facilitators in maternal care and essential newborn care, indicating superior overall HBNC knowledge among ASHA facilitators.

Conclusion: ASHA facilitators demonstrated stronger knowledge of HBNC roles and practices, while knowledge gaps were observed among ASHAs. Competency-based periodic training is essential to improve HBNC knowledge and skills among ASHAs, which in turn can contribute to reducing neonatal mortality and maternal morbidity.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

The Home-Based Newborn Care (HBNC) programme, launched in 2011 under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), aims to reduce neonatal mortality in rural areas with restricted access to care. The programme mandates six visits for institutional deliveries and an additional visit within 24 hours for home deliveries, all conducted by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs). Special attention is given to pre-term, low birth weight, and ill newborns. ASHAs receive an incentive of ₹250 per newborn upon completion of the scheduled home visits. In FY 2023-24, over 1.46 crore (89.3%) newborns received HBNC visits at their doorstep.1

The HBNC strategy, implemented by the Government of India since 2011, aims to reduce newborn deaths occurring within the first seven days of life. It provides a continuum of care for newborns and postnatal mothers, focusing on ASHAs. Key components include home visits, newborn examinations, extra visits for preterm and low birth weight infants, early identification of illness, follow-up for sick newborns, postpartum counselling, recognition of complications, and family planning adoption. HBNC is the primary community-based approach to improving newborn health.2 Globally, neonatal mortality is decreasing, with the rate dropping from 37 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 21 in 2022. This corresponds to a reduction from 5.0 million deaths in 1990 to 2.3 million in 2022, with majority deaths occurring within the first week of life.3

India's neonatal mortality rate is among the highest globally, largely due to inadequate training and health-care infrastructure. Neonatal deaths account for 70% of all infant deaths, underscoring the need for optimal care during the first month of life.4 The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) has implemented several initiatives to reduce child mortality, as India accounts for one-fifth of global live births and one-quarter of neonatal deaths.5 Evidence indicates that most newborns received age-appropriate home visits; however, many mothers were unaware of the HBNC provisions. Moreover, as the visits increased, the quality of ASHA's services declined. Key recommendations include improving training and supervisory mechanisms, and ensuring timely reimbursement of incentives. Health education on newborn care practices and danger signs are also needed.6 According to the Registrar General of India's Sample Registration System (SRS) Statistical Report 2020, the Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) in India declined from 30 to 28 deaths per 1000 live births between 2019 and 2020.7 In Karnataka, the IMR was 19 deaths per 1000 live births8, while Tumkur district reported an infant mortality rate of 21.4 deaths per 1000 live births.9

The District Nutrition Profile for Tumkur, Karnataka reveals significant challenges in child and maternal nutrition. Among the children under five, 40% are stunted, 11% are wasted, and 68% are anaemic. Anaemia is also prevalent among women aged 15-49 years, and nearly 30% of women in this age group are overweight or obese. The report also highlights gaps in exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices. While improvements have been made in healthcare access, strengthening socio-economic factors, including women's education and sanitation, are needed to address malnutrition and related health issues.10

Newborns often die at home due to inadequate care provided by mothers, relatives, or traditional birth attendants. Essential newborn care includes warmth, feeding, skin-to-skin contact, hygiene, and seeking timely assistance from health personnel. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends cleanliness, breathing, thermal protection, breastfeeding, eye care, immunization, illness management, and specialized care for low-birth-weight infants. Evidence shows that home-based care interventions can reduce neonatal mortality by one-third to two-thirds.11

Aims and objectives

1. To estimate the level of knowledge regarding HBNC among ASHAs and ASHA facilitators.

2. To compare the knowledge of HBNC practices between ASHAs and ASHA facilitators.

Materials and Methods

This study aimed to assess the knowledge of ASHAs and ASHA facilitators in Tumkur district, Karnataka. The study was conducted over a period of five months. All participants had received training in HBNC and were invited to the District Training Centre (DTC), Tumkur, for Home-Based Care for Young Child Training. A multi-stage random sampling technique was used, where 25% of PHC-SC-Village-ASHAs in the district of Tumkur were randomly selected. Previous studies report that knowledge of HBNC among ASHAs ranges from 45% to 85%.12-14

A total of 584 participants were included in the study. Permission for conducting the study was obtained from the Reproductive and Child Health Officer (RCHO), the District Health and Family Welfare Office, and the Institutional Ethics Committee. A pre-tested, validated, semi-structured, close-ended, self-administered, application-based questionnaire consisting of multiple-choice questions was developed based on the Government's Training Module 6 (HBNC).15 The questionnaire was validated by obtaining feedback from at least six experts in the field of subject and in questionnaire development. The developed checklist consisted of 10 items on a five-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). The content validity index was calculated using the item level-content validity index (I-CVI), wherein experts rated each item as 0 (irrelevant) or 1 (relevant); an I-CVI value of 0.83 or more was considered indicative of good and sufficient validity. The questionnaire was translated into the vernacular language (Kannada) with the help of a language expert.

The final questionnaire consisted of 29 items, of which 27 were multiple-choice questions with a single correct answer. After validation of the questionnaire by experts, the knowledge scores were categorized as follows: score >14 - good, 7-14 - average, and <7 - poor. Participants were assessed for their knowledge of maternal and essential newborn care.

Results

In this study, a total of 584 community health workers were included, of whom 74 were ASHA facilitators and 510 were ASHAs. The demographic details of both groups are presented in Table 1. The majority of ASHA facilitators (67.5%) and ASHAs (62.94%) were middle-aged (36-45 years). Regarding educational status, 97.3% of ASHA facilitators had completed at least 10th standard, compared to 22.55% of ASHAs. Additionally, 87.84% of ASHA facilitators had more than 10 years of work experience as healthcare workers, whereas this proportion was 59.80% among ASHAs.

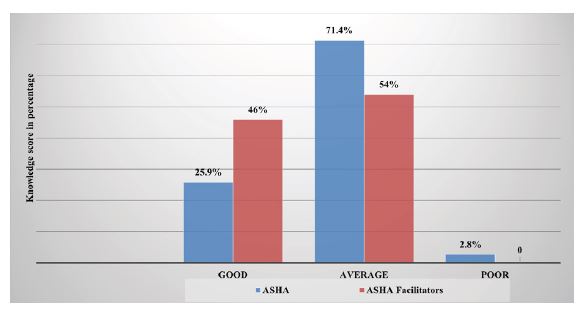

The comparison of HBNC knowledge between ASHAs and their facilitators is presented in Figure 1. ASHA facilitators demonstrated a higher level of knowledge, with 46% (n= 34) scoring in the ‘good’ category, compared to 25.9% (n=132) of ASHAs. None of the ASHA facilitators had poor knowledge scores, whereas 2.8% (n=14) of ASHAs fell into the poor category. A statistically significant difference was observed in the HBNC knowledge levels between the two groups (P = 0.0009).

Table 2 presents a comparison between ASHA facilitators and ASHAs in terms of their knowledge regarding maternal care and essential newborn care. In the domain of maternal care, ASHA facilitators demonstrated significantly higher knowledge, with a mean score of 4.36±0.75 compared to 2.89±1.15 among ASHAs. It was observed that 62.16% of facilitators and 41.17% of ASHAs had correct knowledge on maternal care, and this difference was statistically significant (χ² = 11.56, P = 0.00067). In contrast, for essential newborn care, both groups exhibited relatively similar levels of knowledge, with ASHA facilitators showing slightly higher scores (mean: 10.97±1.30) than ASHAs (mean: 10.26±2.00), and correct knowledge reported in 68.91% of facilitators and 64.11% of ASHAs. This difference, however, was not statistically significant (χ² = 0.652, P = 0.419), indicating no meaningful variation in essential newborn care knowledge between the two groups.

Discussion

In our study, both ASHA facilitators and ASHAs were predominantly in the middle age group (36-45 years). This age distribution is consistent with the findings of Pandit SB et al., who reported that most ASHAs belonged to the 31-40 years age group (48.6%), indicating that middle-aged individuals are often preferred for community health roles due to their perceived stability, maturity, and ability to handle responsibilities effectively.12 The observed disparity in education levels between facilitators and ASHAs is noteworthy, as higher educational qualifications have consistently been linked with better healthcare knowledge and improved performance.16

The work experience of both groups further highlights the role of tenure in enhancing knowledge and skills. A majority of ASHA workers (59.80%) and facilitators (87.84%) had over 10 years of experience, with facilitators having a significantly higher long-term experience. This aligns with a study by Devi RS et al., which reported that approximately 59% of ASHAs had more than 10 years of work experience. The greater experience among facilitators likely contributes to their superior performance in maternal and newborn care domains in the present study. Similar findings have been reported in other low- and middle-income countries, where skilled community health workers had been shown to deliver more effective healthcare services.17

In the present study, ASHA facilitators demonstrated a higher proportion of good knowledge in maternal care (62.16%) and essential newborn care (68.91%) compared to ASHAs, who scored 41.17% and 64.11%, respectively. The facilitators’ comparatively higher educational qualifications and longer work experience may explain their superior knowledge of HBNC. These findings are consistent with studies by Sharma A et al.,18 and Bhutta ZA et.,19 al.,which reported that community health workers with higher education and greater experience perform better in delivering maternal and child health services.

The facilitators’ higher educational qualifications and extensive experience likely enable them to better understand and apply critical healthcare practices, contributing to improved maternal and newborn care outcomes. This significant disparity aligns with global evidence suggesting that higher educational attainment and longer work experience are associated with enhanced healthcare knowledge and performance.20-21

The implications of these findings are significant for policymakers and program managers in India and similar settings. Strengthening the educational qualifications and providing continuous training for ASHA workers could help bridge the knowledge gap between workers and facilitators. Additionally, recognizing the value of experience and creating opportunities for career advancement may further enhance the effectiveness of ASHA workers in delivering community healthcare services. Similar strategies have been successfully implemented in other countries, such as Ethiopia and Bangladesh, where targeted training and mentorship programs have improved the performance of community health workers.22-23

Future research should identify the specific training needs of ASHA workers and assess the impact of targeted interventions. Qualitative studies can offer deeper insights into the challenges they encounter while delivering maternal and newborn care services. Addressing these gaps will help strengthen India's community health workforce and improve healthcare outcomes.

Strength and Limitations

The current study included a substantial number of ASHAs and ASHA facilitators as participants, enabling a comprehensive assessment of their overall knowledge regarding Home-Based Newborn Care. However, it did not evaluate the practical application of their knowledge in field settings. Additionally, further research involving other categories of community health workers is needed to gain a better understanding of the programme’s implementation.

Conclusion

In the present study, ASHA facilitators demonstrated good knowledge scores in maternal care whereas ASHAs exhibited average levels of knowledge. However, both groups showed comparable knowledge scores in essential newborn care. Periodic training on HBNC is essential for community health workers to reduce morbidities among infants and postnatal mothers. The key limitation of the study was the inability to assess the practical implementation of the learnt skills. Therefore, it is recommended that programme officers assess HBNC knowledge prior to initiating Home-Based Care for Young Child (HBYC) training, for reducing under-five morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgement

We thank all the ASHAs and ASHA facilitators for giving their time and responses. We thank Interns for helping in data collection.

Source of funding

Nil

Conflicts of Interest

None

Supporting File

References

1. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Home-Based Newborn Care (HBNC). [cited 2025 Feb 27]. Available from: https://hbnc-hbyc.mohfw.gov.in/about/hbnc.

2. National Rural Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Home Based Newborn Care: Operational Guidelines. Nirman Bhavan, New Delhi; 2011. Available from: https://nihfw.ac.in/Doc/NCHRC-Publications/ Operational%20Guidelines%20on%20Home%20 Based%20Newborn%20Care%20(HBNC).pdf.

3. World Health Organization. Newborn mortality [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ newborn-mortality.

4. Government of India. Neonatal mortality rate - India [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 10]. Available from: https://data.gov.in/catalog/neo natal mortality rateindia?filters%5Bfield_catalog_reference%5D= 89175&format=json&offset=0&limit=6&sort%5B created%5D=desc.

5. Sankar MJ, Neogi SB, Sharma J, et al. State of newborn health in India. J Perinatol 2016;36(s3):S3-S8.

6. UNICEF India. The infant and child mortality India report [Internet]. New Delhi; UNICEF; 2019. p. 1‑13. Available from: http://unicef.in/ PressReleases/374/ The Infant and Child Mortality India Report.

7. Pathak PK, Singh JV, Agarwal M, et al . Study to assess the home-based newborn care (HBNC) visit in rural area of Lucknow: A cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care 2021;10:1673-7.

8. Registrar General of India. Sample Registration System Statistical Report 2020. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General, Ministry of Home Affairs; 2022 [cited 2025 Feb 27]. Available from: https:// censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/44376

9. Statista. Infant mortality rate in Karnataka, India [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Feb 27]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1050416/ india-infant-mortality-rate-karnataka.

10. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019–20: Karnataka. Mumbai: IIPS; 2021. Available from: https://data.opencity.in/dataset/530ee93a-d24c- 43df-b90b-272a067d5a4e/resource/4104925d- 8122-4199-932f-fb046d607d7d/download/ karnataka-nhfs.pdf.

11. World Health Organization. Counselling for maternal and newborn health care: A handbook for building skills. Genève, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK304190/?report=printable.

12. Pandit SB, Boricha BG, Mhaske A. To assess the knowledge & practices regarding home based newborn care among accredited social health activist (ASHA) in rural area. International Journal of Health Sciences & Research 2016;6 (12):205-209.

13. Shah N, Mohan D, Agarwal S, et al. Novel approaches to measuring knowledge among frontline health workers in India: Are phone surveys a reliable option? PLoS One 2020;15(6):7.

14. Choudhary ML, Joshi P, Murry L, et al. Knowledge and skills of accredited social health activists in home-based new-born care in a rural community of Northern India: an evaluative survey. Int J Community Med Public Health 2020;8(1):334-38.

15. National ASHA mentoring group. ASHA Module 6: Skills that save lives [Internet]. New Delhi: National Health Systems Resource Centre; [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://nhsrcindia. org/sites/default/files/202105/Skills%20that%20 Save%20Lives%20ASHA%20Module%206%20 English.pdf.

16. World Health Organization. Community health workers: What do we know about them? [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2018 [cited 2025 Aug 10]. Available from:https://www.who.int/publications/i/ item/what-do-we-know-about-community-health-workers-a-systematic-review-of-existing-reviews.

17. Devi RS, Pugazhendi S, Juyal R, et al. Evaluation of existing Home-Based Newborn Care (HBNC) services and training for improving performance of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) in rural India: A multiple observation study. Midwifery [Internet]. 2023;116(103514):103514. Available-from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. midw.2022.103514.

18. Sharma A, Gupta S, Mehra S. Knowledge and practices of ASHA workers regarding maternal and child health in rural India. J Family Med Prim Care 2020;9(2):1005-1010.

19. Bhutta ZA, Lassi ZS, Pariyo G, et al. Global experience of community health workers for delivery of health related millennium development goals: A systematic review, country case studies, and recommendations for integration into national health systems. Geneva: WHO; 2013.

20. Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, et al. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health 2018;16(1):39.

21. Pandey S, Karki S, Baral N, et al. Knowledge and practices of community health workers in Nepal: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19(1):618.

22. Kok MC, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, et al. Which intervention design factors influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2015;30(9):1207-1227.

23. Rahman SM, Ali NA, Jennings L, et al. Factors affecting recruitment and retention of community health workers in a newborn care intervention in Bangladesh. Hum Resour Health 2017;15(1):51.