RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Department of Community Medicine, Maharishi Markandeshwar Medical College, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India

2Dr. Amal Titto V Augustine, Department of Community Medicine, Maharishi Markandeshwar Medical College, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India.

3Department of Community Medicine, Maharishi Markandeshwar Medical College, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India

4Department of Community Medicine, Maharishi Markandeshwar Medical College, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India

5Department of Community Medicine, Maharishi Markandeshwar Medical College, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Amal Titto V Augustine, Department of Community Medicine, Maharishi Markandeshwar Medical College, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, India., Email: amaltittoaugustine@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Obesity is an escalating global health concern with profound implications for individuals and societies, particularly among young adults. It is associated with a range of serious health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and certain types of cancer.

Aims/Objectives: The study aims to assess the prevalence of obesity among university students in Hyderabad, identify associated factors, and examine its relationship with lifestyle and dietary habits.

Methods: This cross-sectional study investigates the prevalence and determinants of obesity among 355 university students aged 18-25 years in Hyderabad, India. Using a structured questionnaire and anthropometric measurements, the study explores associations between obesity and various demographic, lifestyle, and behavioral factors, including meal-skipping, exercise duration, sleep patterns, and transportation methods.

Result: Obesity prevalence was 27.04%, with significant associations observed between obesity and age (P = 0.037), gender (P = 0.001), exercise duration (P = 0.031), water intake (P = 0.035), and mode of transportation (P < 0.0001). Obesity was more prevalent among older students, males, hostel residents, those with a family history of obesity, and those who frequently skipped meals or consumed high-calorie foods.

Conclusion: The findings display how demographic and lifestyle factors influence BMI, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions in universities to address obesity-related behaviors. This study advocates for comprehensive public health strategies aimed at mitigating obesity risk through health awareness, dietary improvements, and promoting physical activity among students.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

The global prevalence of obesity has increased to alarming levels, posing major public health challenges. In 2022, approximately one-eighth of the world's population was classified as obese. Adult obesity rates have more than doubled since 1990, and the incidence among adolescents has quadrupled. That year, 2.5 billion adults were overweight, including 890 million who were obese. Overall, 43% of adults aged 18 and above were overweight, and 16% were obese. The trend is equally concerning in younger age groups: 37 million children under five were overweight, and more than 390 millionchildren and adolescents aged 5-19 were overweight, including 160 million who were obese.1

According to a recent projection from the World Obesity Federation, global obesity prevalence is expected to rise sharply, with an estimated one billion people living with obesity by 2030. This includes forecasts that one in five women and one in seven men will be affected.2

The growing prevalence of obesity imposes a significant burden on economies and healthcare systems. In addition to the direct financial costs of treating obesity and related conditions, these health issues have been found to reduce the productive working years of both men and women by 4 to 9 years across countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. This substantial loss of productivity represents a major challenge for these nations, as it undermines economic growth and development. Additionally, the strain on healthcare systems due to the rising rates of obesity-related diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers, further exacerbates the public health and economic consequences of this global epidemic.3

The personal, social, and economic consequences of obesity are substantial. It is estimated to contribute to 5% of all global deaths. Economically, obesity imposes an extraordinary burden of approximately $2 trillion worldwide, comparable to the costs associated with smoking and armed conflict. Growing evidence also indicates that obesity can diminish socioeconomic productivity, as affected individuals often face reduced earning capacity and lower workforce participation. Given its far-reaching impact, there is an urgent need for comprehensive strategies to address this escalating public health crisis.4

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that obesity as a comorbid condition can exacerbate mortality and complications associated with infectious diseases.5

According to prior reports, the South Asian region, which encompasses India, exhibits one of the most rapidly escalating obesity rates globally. India, a key country within the South Asian region, has seen a concerning surge in obesity prevalence in recent years. Current estimates suggest that India is home to approximately 135 million individuals living with obesity, making it one of the countries with the highest obesity burden worldwide.6

Several factors contribute to obesity among university students. Meal skipping is prevalent, with many failing to meet recommended nutrient intake levels. Research has linked higher body mass index to insufficient physical activity, unhealthy high-calorie diets, and sedentary lifestyles. Eating habits, physical activity, sleep patterns, water intake, family history of obesity, and personal behaviors all impact the prevalence and determinants of BMI in this population. Multiple studies have reported elevated rates of overweight and obesity in this group.6-13

This study aims to assess the prevalence of obesity among university students in Hyderabad and identify the associated factors. It specifically examines how lifestyle and dietary habits such as meal skipping, exercise rou-tines, sleep patterns, and hydration levels relate to obesity across different demographic groups, including age, gender, year of study, and living arrangements.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study undertaken at the MNR medical college, Hyderabad, between August 2024 and September 2024. All students provided written informed consent for their participation in the study.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Committee on 24th July 2024. Simple random sampling was used to select 403 first to fourth-year academic level undergraduate MBBS as well as BPT student aged 18- 25 years. Students who were feverish, and students with osteoporosis or oedema (swelling in the body) were excluded.

The required sample size to assess overweight/obesity prevalence among students was calculated assuming P = 0.16 from WHO data, based on an estimated prevalence of obesity of 16%, a margin of error of 4%, and a 95% confidence interval, the initial sample size was calculated to be 322.1 Considering a 10% non-response rate the adjusted sample size is (322+33) 355. The final sample size was rounded to 355. Data collection was performed using a structured questionnaire divided into sections covering demographic information (age, gender, year of study, and course), health and medical history (family history of obesity, current medication usage, and chronic conditions), lifestyle factors (dietary habits, physical activity levels, smoking and alcohol consumption, sleep patterns, and stress levels), and anthropometric measurements (height and weight, with BMI calculated using the formula: BMI = Weight (kg) / Height (m)2). According to the Southeast Asian classification, BMI ranges are defined as follows: underweight is less than 18.5, normal is between 18.5 and 22.9, pre-obese (overweight) is between 23 and 24.9, Class I obesity is between 25 and 27.49, Class II obesity is between 27.5 and 32.49, and Class III obesity is 32.5 or greater.14

Data analysis

Data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using SPSS software. Descriptive statistics summarized demographic characteristics, while the prevalence of overweight and obesity was determined by the proportion of students with BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m² and BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m², respectively. Statistical analysis involved computing frequency distributions, means, and standard deviations, using chi-square tests, t-tests, ANOVA, and logistic regression to identify significant predictors of obesity while adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

The study included 355 participants, comprising 241 females (67.9%) and 114 males (32.1%). Of these, 115 students (32.4%) were under 21 years of age, while 240 (67.6%) were 21 years or older. The mean age was 21.2 ± 1.31 years (range: 18-24), reflecting a relatively young and homogeneous sample. Participants had a mean weight of 59.68 ± 13.14 kg (range: 38–108 kg) and a mean height of 162.92 ± 8.94 cm (range: 142-200 cm), indicating moderate variability in body composition and stature. The mean BMI was 22.36 ± 3.54 (range: 16.73- 31.56), with most students falling within the healthy BMI range.

Academically, 163 students (45.9%) were in their 2nd year, 112 (31.5%) in their 3rd year, and 80 (22.5%) in their 4th year. Regarding living arrangements, 214 (60.3%) were day scholars, and 141 (39.7%) were hostel residents. For transportation, 206 students (58.0%) walked to campus, 105 (29.6%) traveled by bus, and 44 (12.4%) used their own vehicles.

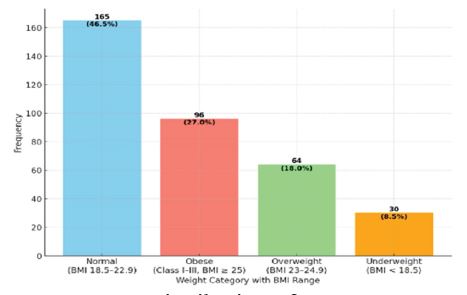

The BMI distribution of the participants showed that 46.5% (165) were of normal weight, 27.0% (96) were obese, 18.0% (64) were overweight, and 8.5% (30) were underweight. Age was significantly associated with BMI (P = 0.037). Students under 21 years had higher rates of normal weight (52.2%) and obesity (30.4%), whereas those aged 21 years and above showed more varied BMI patterns, including higher rates of overweight (20.0%) and underweight (10.8%).

Gender also significantly influenced BMI (P = 0.001). Males exhibited higher obesity rates (38.6%) compared to females (21.6%), while females showed a higher proportion of normal BMI (53.5% vs. 31.6%). Mode of transportation was another strong determinant (P = 0.000056). Bus users had the highest proportion of normal weight (50.5%), walkers showed moderate BMI distribution (47.6% normal weight), and students using personal vehicles (bike/car) had the highest obesity rates (38.6%) and the lowest normal weight percentage (31.8%), indicating that active transportation may support healthier BMI outcomes.

Personal habits had a pronounced impact on BMI, with students reporting multiple habits-such as smoking, alcohol, and drug use-showing extremely high obesity rates (71.4%). Exercise duration also significantly influenced BMI (P = 0.031). Those exercising less than 30 minutes per day had higher normal weight percentages (49.3%) and lower obesity rates (23.3%). Surprisingly, students exercising for 30 minutes or more reported higher obesity rates (29.8%) and slightly lower normal weight levels (44.4%), suggesting that consistency and exercise quality may matter more than duration alone. Overall, these findings underscore the complex interplay of demographic, lifestyle, and behavioral factors influencing BMI among university students (Table 1).

Water intake was another significant factor (P = 0.035). Participants consuming less than 2 liters per day had the highest proportion of normal weight (50.7%), while those drinking more than 2 liters showed higher obesity rates (35.6%). Students consuming exactly 2 liters demonstrated moderate BMI distribution (44.2% normal weight), indicating that optimal hydration may support better weight management.

Table 2 shows several significant associations between eating habits and BMI categories. Breakfast skipping was significantly related to BMI (P = 0.035), with daily skippers more often falling into the normal weight (50%) and obese (31.8%) categories. Lunch skipping also showed a significant association (P = 0.05), with 62.5% of daily lunch skippers classified as obese. Dinner skipping was significant as well (P = 0.043), although only a small number of participants skipped dinner daily.

Eating outside exhibited the strongest association with BMI (P = 0.000075), with 60.6% of individuals who ate outside daily being obese. Munching between meals was also significantly associated with BMI (P = 0.004), with daily snackers showing higher obesity rates (34.5%).

Conversely, some eating behaviors showed no significant relationship with BMI, including chocolate consumption (P = 0.714), watching TV while eating (P = 0.93192), and junk food intake (P = 0.37878).

Overall, these findings suggest that meal timing and the frequency of eating outside have stronger links to BMI than specific food choices or eating while watching TV.

The bar chart displays the distribution of weight categories among 355 individuals, with each category labeled by frequency, percentage, and BMI range (Figure 1). The largest group is the normal weight category (BMI 18.5-22.9), comprising 165 individuals (46.5%), indicating that nearly half of the participants fall within a healthy weight range. The next largest group is the obese category (BMI ≥ 25), which includes 96 individuals (27.0%). The overweight or pre-obese category (BMI 23-24.9) accounts for 64 individuals (18.0%), representing those slightly above the normal range. The smallest group is the Underweight category (BMI < 18.5), with 30 individuals (8.5%).

Discussion

Among our participants, the BMI suggests a tendency toward weight gain as students age, likely reflecting cumulative lifestyle changes over time. Similar age-related trends have been reported in previous studies. Venkatrao et al., observed a higher prevalence of obesity among individuals over 40 years (45.81%) compared with those under 40 years (34.58%).15 Chenji et al., also reported a significant difference, noting a higher obesity prevalence among males (P = 0.003).12 Data from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) further support this trend, showing the highest obesity prevalence among middle-aged adults aged 40-59 years, followed by younger adults.11 Prevalence is considerably lower among adolescents (20.6%) and children aged 2-5 years (13.9%).

In our study, female students predominantly fell within the normal BMI category, whereas obesity was more common among males. This difference may reflect gender-specific lifestyle factors such as dietary patterns and physical activity levels. However, findings from the literature present a mixed picture regarding gender-related differences in obesity. For instance, Lee et al., reported a higher prevalence of obesity among women (41.1%) than men (37.9%).16 Similarly, Obirikorang et al., found that females had significantly higher odds of obesity, between 1.8 and 2.5 times, compared with males.17 In contrast, Dampetla et al., observed slightly higher obesity rates in males (27% vs. 26%), although females exhibited a greater prevalence of combined obesity when BMI and waist circumference were considered together (57% vs. 43%).9 Behera et al. further highlighted sex-based differences, reporting higher body fat percentages in females (34.23%) compared with males (20.77%).13 Anupama et al., also demonstrated that 61% of females had a waist-hip ratio ≥0.85, whereas only 20% of males had a waist-hip ratio ≥0.9.10 Taken together, these variations across studies indicate that gender differences in obesity remain inconclusive, likely influenced by differing assessment methods, population characteristics, and lifestyle factors.

Our study indicates that obesity prevalence is higher among third-year and fourth-year students, who constitute 39.6% and 45.8% of the obese group, respectively. In contrast, second-year students account for nearly half (49.7%) of those with a normal BMI. These findings suggest that academic progression may be associated with increasing BMI, potentially due to heightened academic pressure, reduced physical activity, or lifestyle changes that occur as students advance through their programs. This trend aligns with observations by Obirikorang et al., who reported a higher prevalence of obesity among students in advanced academic years, particularly those in the third and fourth years.17 This pattern may also partly reflect the influence of increasing age, as discussed earlier.11,12,15

In our study, obesity was more prevalent among hostel residents, with 72.9% of obese students being hostelites (70/96). This may be due to limited dietary control and reduced physical activity within hostel settings. Similar patterns have been reported in the literature. Lee A et al., found that greater exposure to fast food outlets and limited access to healthy food options (“food deserts”) are associated with higher obesity rates.16 This may explain the increased prevalence observed among hostelites. Premlal KS et al. further highlighted poor dietary habits among college students, noting that 99.5% consumed bottled drinks and junk foods weekly, 54% consumed fried items 1-2 times per week, and 28% consumed them 3-5 times weekly, behaviours that heighten obesity risk.

Moreover, Premlal KS et al., reported that students spent an average of 48.5 hours per week on sedentary activities, with only 2.9 hours devoted to physical activity. Smoking (4%) and alcohol consumption (2.5%) were also noted.8 These lifestyle patterns align with our findings, reinforcing that personal habits significantly influence obesity risk among college students.

Collectively, these observations highlight the need to address both dietary practices and physical activity levels within hostel environments. Limited control over food quality, combined with poor dietary choices and predominantly sedentary lifestyles, poses a substantial challenge in managing obesity among hostel-residing students. Targeted interventions should therefore focus on improving access to healthier food options, increasing opportunities for regular physical activity, and raising awareness about obesity-related health risks.

Our study indicates that alcohol consumption is more prevalent among obese students (36.5%, 35/96) com-pared to those with a normal BMI (14.5%, 24/165). Additionally, 20.8% of obese students (20/96) reported engaging in multiple high-risk habits, including smoking, alcohol, and drug use, suggesting a clustering of unhealthy behaviors that may contribute to weight gain. These findings align with Anupama et al., who observed poor dietary patterns among medical students, including daily junk food intake (6.5%), daily consumption of sweets or chocolate (1.5%), frequent intake of sweetened beverages (10%), and high coffee consumption (>4 cups/ day in 9.5% of students).10

In our study, daily eating outside was more common among obese individuals (20.6%), whereas occasional outside eating was the predominant pattern across all BMI groups, reaffirming its widespread nature. Interestingly, daily chocolate consumption was highest among those with a normal BMI, while a substantial proportion of obese and overweight students reported never consuming chocolate. Munching between meals every day was slightly more common among individuals with a normal BMI, although occasional snacking was frequent across all categories. Likewise, occasional junk food consumption was most common in all BMI groups, whereas daily junk food intake was relatively low but highest among obese students.

Sedentary behaviors also contributed to weight differences: watching TV while eating every day was most common among obese students, followed by those with a normal BMI, while underweight participants reported the lowest engagement in this behavior.

Overall, these findings suggest that a combination of poor dietary habits, particularly frequent outside eating, and sedentary behaviors contribute to the higher prevalence of obesity among students. Interventions aimed at improving diet quality, discouraging unhealthy snacking, and reducing sedentary behaviors such as screen time during meals are essential for effective obesity prevention in this population.

Our study indicates that obese students have a higher prevalence of alcohol consumption (36.5%, 35/96) compared to those with a normal BMI (14.5%, 24/165). Additionally, 20.8% of obese students (20/96) reported engaging in multiple high-risk habits, including smoking, alcohol, and drug use, suggesting that such clustered behaviors may contribute to weight gain. These findings align with Anupama et al., who reported poor dietary habits among students, including daily junk food consumption (6.5%), daily intake of sweets (1.5%), sweetened beverages (10%), and high caffeine intake (>4 cups/day in 9.5%).10

A substantial proportion of obese individuals in our study reported eating outside daily (20.6%), while occasional outside eating was common across all BMI groups. Daily chocolate consumption was highest among students with normal BMI, whereas many obese and overweight students reported never consuming chocolate. Daily munching between meals was more common among normal BMI individuals, although occasional snacking was prevalent across all groups. Likewise, occasional junk food consumption was the dominant pattern for all BMI categories, with daily junk food intake remaining low but highest among obese participants. Watching TV during meals daily was most common among obese students, followed by those with normal BMI, indicating a link between sedentary behaviors and higher body weight.

Dietary patterns further revealed that a mixed diet was the most common across BMI groups, with 65.5% of normal-weight students (108/165) following it. However, only 8.3% (8/96) of obese students were vegetarians, suggesting a possible protective effect of vegetarian diets. Obesity was more prevalent among students consuming millets (45.8%) and rice (47.9%) as staple foods. These findings align with Jiao et al., who emphasized that modern eating habits, poor diet quality, and environmental influences drive obesity, and that personalized nutrient-dense diets, such as low-calorie or plant-based patterns, can improve metabolic outcomes.18

Meal-skipping behaviors were also significantly associated with BMI categories in our study. A higher percentage of obese individuals reported skipping breakfast, lunch, and dinner compared to those with normal BMI. Notably, 14.6% of obese students skipped breakfast daily, whereas 43.3% of normal-weight participants never skipped breakfast. These findings parallel Anupama et al., who demonstrated that breakfast skipping is common and significantly associated with obesity.10

Sleep duration also differed across BMI categories. Short sleep (<6 hours) was reported by 29.2% of obese students (28/96) compared to only 8.5% of normal-weight students. Oversleeping (>8 hours) was also more common among obese individuals (33.3%). These findings are consistent with Beccuti et al., who linked poor sleep quality to higher BMI, particularly among young women, and Sa et al., who found increased odds of both short and long sleep duration among individuals with obesity.19,7

Water intake patterns demonstrated that lower water consumption (<2 liters/day) was more prevalent among obese students (50%, 48/96) than among normal-weight individuals (29.1%, 48/165). This contrasts with the findings of Jaewon Khil et al., who reported that higher total water intake (>1 liter/day) was associated with higher BMI and waist circumference, and that water consumed before bedtime was associated with lower BMI. They also found that drinking cold water, compared to room-temperature water, correlated with higher BMI.20

In conclusion, our study highlights the multifactorial nature of obesity among students, driven by unhealthy dietary habits, frequent meal-skipping, sedentary behaviors, poor sleep patterns, and suboptimal water consumption. Personalized interventions promoting regular meals, nutrient-dense diets, reduced screen time during eating, adequate sleep, and balanced water intake are essential for effective obesity prevention and management in this population. Further research is warranted to explore how these interrelated lifestyle factors contribute to long-term weight trajectories among college students.

Our study indicates that students commuting by bike or car have higher obesity rates, with 61.5% of obese students (59/96) using private vehicles. In contrast, 44.8% of normal BMI students (74/165) walk or commute by bus, forms of active transport associated with lower obesity prevalence. These findings suggest that incorporating physical activity into daily routines through active commuting may help maintain a healthier BMI. This is supported by Lee A et al., who reported that high walkability is associated with reduced obesity rates, particularly in urban environments.16 Similarly, Patil et al. found that private vehicle use increases obesity risk, whereas active commuting significantly lowers it, especially in high-density areas with high walkability scores.21 Together, these findings underscore the importance of promoting walking, cycling, and public transportation to support healthier lifestyles and reduce obesity risk among students.

Family history also appears to play a substantial role. Among obese students in our study, 8.3% reported both maternal and paternal history of obesity, while 62.5% reported maternal history alone, indicating a strong familial or genetic predisposition. The influence of genetic and shared environmental factors on obesity is well-established. Anupama et al ., reported a significant association between parental obesity and student BMI, suggesting that both heredity and shared lifestyle patterns contribute to obesity risk.10 Obirikorang et al.,further confirmed that individuals with a family history of obesity have markedly higher odds of developing obesity due to the combined impact of genetics, dietary habits, physical activity patterns, and other shared lifestyle behaviors.¹⁷ These findings highlight the need to account for familial predispositions when designing obesity prevention and intervention programs.

Physical activity patterns also differed significantly across BMI categories. A larger proportion of normal BMI students engaged in outdoor exercise (63%) compared to obese students (41.7%). Additionally, 58.2% of normal BMI students exercised for at least 30 minutes daily, while only 32.3% of obese students met this duration. This demonstrates that both exercise type and duration influence BMI. Dampetla et al., support this observation, showing a significant negative correlation between exercise and waist circumference (r = –0.292, P < 0.001), suggesting that increased physical activity contributes to reductions in central obesity.9 These findings reinforce the importance of incorporating consistent, adequate physical activity into students’ daily routines.

Overall, our results demonstrate that obesity in students is influenced by multiple interacting factors, including commuting patterns, family history, and physical activity levels. Given the well-known association between obesity and conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases, early preventive strategies during university years are essential. By promoting active commuting, encouraging regular exercise, and addressing genetic and lifestyle-related risks, institutions can significantly reduce long-term obesity-related health complications and foster healthier, more productive communities.

Limitations

The study has several limitations, including its cross-sectional design, which prevents establishing causality; potential recall and social desirability bias from self-reported data; and limited generalizability, as it was conducted in a single medical college. Despite these constraints, the findings provide meaningful insights into the prevalence and determinants of obesity among medical students and can help guide targeted interventions and public health strategies.

The study’s limitations include its reliance on self-reported data, which may introduce recall and social desirability bias. Moreover, using BMI as the sole indicator of obesity may overlook important variations in body composition, such as muscle mass and fat distribution.

Conclusion

This study identifies a high prevalence of obesity among university students in Hyderabad and demonstrates significant associations between obesity and various demographic, lifestyle, and behavioral factors. Age, gender, transportation habits, family history of obesity, and lifestyle choices, such as meal skipping, sedentary behavior, and inadequate hydration, were key contributors to higher BMI. Obesity was more common among older students, males, hostel residents, and those using sedentary commuting methods or consuming high-calorie diets, whereas active commuting and moderate exercise were linked to healthier BMI levels. Although limited to a single medical college, these findings provide valuable insights for developing targeted public health interventions to reduce obesity and promote healthier lifestyles among young adults. Future research should extend these observations across diverse student populations and incorporate longitudinal designs to better understand causal pathways behind obesity-related behaviors.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest

Source of funding

Nil

Supporting File

References

1. WHO. Obesity and overweight [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2024 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www. who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

2. World Obesity. World Obesity Atlas 2022. [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 5]. Available from: https:// www.worldobesityday.org/assets/downloads/ World_Obesity_Atlas_2022_WEB.pdf

3. Okunogbe A, Nugent R, Spencer G, Ralston J, Wilding J. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for eight countries. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(10):e006351.

4. McKinsey. How the world could better fight obesity [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2024 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/ our-insights/how-the-world-could-better-fight-obesity

5. World Obesity. COVID-19-and Obesity: The 2021 Atlas. [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 5]. Available from:https://www.worldobesityday.org/assets/ downloads/COVID-19-and-Obesity-The-2021- Atlas.pdf

6. Pradeepa R, Anjana RM, Joshi SR, et al. Prevalence of generalized & abdominal obesity in urban & rural India-the ICMR-INDIAB Study (Phase-I) [ICMR-NDIAB-3]. Indian J Med Res 2015;142(2):139-50.

7. Sa J, Choe S, Cho B young, et al. Relationship between sleep and obesity among U.S. and South Korean college students. BMC Public Health 2020;20(1):96.

8. Premlal KS, Bhanushali VV, Nagalingam S. A cross sectional study to evaluate the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among college students aged 18-25 years in and around Calicut. International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health 2018;5(7):2829-34.

9. M SS, Dampetla S. Burden of combined obesity among students of a medical college in Guntur city of Andhra Pradesh. Public Health Review: International Journal of Public Health Research 2019;6(3):105-11.

10. M A, Iyengar K, S RS, S RM, P V, Pillai G. A study on prevalence of obesity and life-style behaviour among medical students. International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health 2017;4(9):3314-8.

11. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief 2017;(288):1-8.

12. Chenji SK, Rao CR, Sivanesan S, Kamath V, Kamath A. Cross-sectional analysis of obesity and high blood pressure among undergraduate students of a university medical college in South India. Fam Med Com Health 2018 May 1;6(2).

13. Behera S, Mishra A, Esther A, Sahoo A. Tailoring Body Mass Index for Prediction of Obesity in Young Adults: A Multi-Centric Study on MBBS Students of Southeast India. Cureus. 2021 Jan 8;13(1):e12579.

14. Haam JH, Kim BT, Kim EM, et al. Diagnosis of Obesity: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome 2023;32(2):121.

15. Venkatrao M, Nagarathna R, Majumdar V, Patil SS, Rathi S, Nagendra H. Prevalence of Obesity in India and Its Neurological Implications: A Multifactor Analysis of a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Ann Neurosci 2020;27(3-4):153-61.

16. Lee A, Cardel M, Donahoo WT. Social and Environmental Factors Influencing Obesity. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000 [cited 2024 Nov 5]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278977/

17. Obirikorang C, Adu EA, Anto EO, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of obesity among undergraduate student population in Ghana: an evaluation study of body composition indices. BMC Public Health 2024;24(1):877.

18. Jiao J. The Role of Nutrition in Obesity. Nutrients 2023;15(11):2556.

19. Beccuti G, Pannain S. Sleep and obesity. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care 2011;14(4):402.

20. Khil J, Chen QY, Lee DH, Hong KW, Keum N. Water intake and obesity: By amount, timing, and perceived temperature of drinking water. PLOS ONE 2024;19(4):e0301373.

21. Patil GR, Sharma G. Overweight/obesity relationship with travel patterns, socioeconomic characteristics, and built environment. Journal of Transport & Health 2021;22:101240