RGUHS Nat. J. Pub. Heal. Sci Vol No: 10 Issue No: 4 eISSN: 2584-0460

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Department of Community Medicine, Oxford medical College Hospital & Research Centre, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

2Department of Community Medicine, Sapthagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

3Department of Community Medicine, Sapthagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

4Dr. Renuka Venkatesh, Department of Community Medicine, Sapthagiri Institute of Medical Sciences & Research Centre, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India.

5Department of Community Medicine, Oxford medical College Hospital & Research Centre, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding Author:

Dr. Renuka Venkatesh, Department of Community Medicine, Sapthagiri Institute of Medical Sciences & Research Centre, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India., Email: renukaprithvi6@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Adolescents constitute about one-fourth of India’s population (243 million). Many serious health issues in adulthood have their origins in adolescence. The health of adolescents has long been the weakest pillar in the continuum-of-care approach, and has often been ignored, contributing to an increased disease burden. Recognizing this, India incorporated “A” (Adolescents) into the national programme, now known as ‘Reproductive Maternal Neonatal and Child Health programme +A’.

Aim: To determine the morbidity profile of adolescent boys and girls.

Methods : A cross-sectional study was carried out among school/college-going adolescents in the rural field practice area attached to Community Medicine Department of a teaching medical college. A total of 912 students were included after obtaining consent from their parents. Data were collected through interviews using a pre-tested questionnaire that gathered information on sociodemographic profile, the history of various morbid conditions. This was followed by measurement of weight and height, hemoglobin estimation, and testing of vision. Data were entered in Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages were employed, and the associations between variables were studied using the Chi-square test.

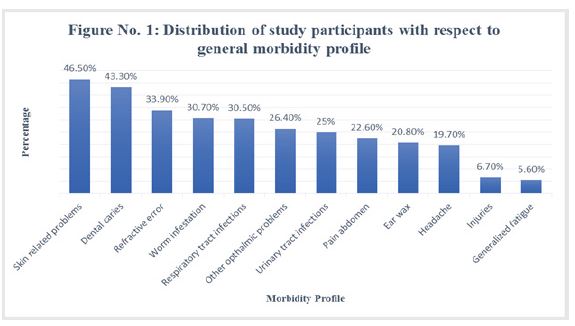

Results: The most common morbid conditions among adolescents were skin-related problems (46.5%), refractive errors (33.9%), worm infestation, and respiratory tract infections.

Conclusion: The majority of adolescents were found to have at least one morbid condition

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Approximately one in six people worldwide is an adolescent (about 1.3 billion), and they constitute about 1/6th of India’s population.1 India has an estimated 253 million adolescents aged 10-19 years. This population group is in a transitional stage of life and requires adequate nutrition, education, counselling, and guidance to ensure healthy growth into adulthood. They are vulnerable to numerous preventable and manageable health issues, including unintended pregnancies, risky sexual behaviors that may result in STI/HIV infections, nutritional deficiencies such as malnutrition, anemia, and obesity, along with substance abuse involving alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, psychological challenges, and various forms of injuries and violence.2

Overall morbidity and mortality among adolescents are increasing due to varied reasons. Among children aged 10–14 years, mortality patterns are largely dominated by infectious diseases. In older adolescents and young adults, however, there is a shift from childhood infectious diseases to causes such as accidents and injuries, self-harm, and interpersonal violence, according to WHO factsheet on adolescent health. Half of all mental health disorders in adulthood begin by the age of 18, yet most cases remain undetected and untreated.3

As per NFHS-5 (National Family Health Survey) data, approximately 59.1% of adolescent girls and 31.1% of adolescent boys are anaemic.4 The overall prevalence of obesity is 5.74%, with rates of 4.4% among boys and 8.8% among girls. The prevalence of underweight is 42%, with 52% among girls and 25.6% among boys. In India, numerous studies conducted among school going adolescents have identified common morbid conditions such as anaemia (23%-78%), dental problems (10%- 80%), refractive errors (6%-23%), skin diseases (5%- 19%), and respiratory tract infections (5%-17%), among others.5

Adolescent health problems constitute a significant share of overall morbidity, yet many remain unrecognized and inadequately addressed, thereby increasing the disease burden. The Government of India acknowledges the need to enhance adolescent's health-seeking behavior has introduced several programmes, including Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) and the School Health & Wellness Programme. Since the health status of this age group significantly influences the country’s overall health, mortality and morbidity patterns, and population growth trends, prioritizing adolescent reproductive and sexual health is crucial. Such investments contribute directly to realizing India’s demographic dividend, as healthy adolescents represent a vital human resource for the nation’s economy.

Several studies have been conducted to investigate the morbidity status of adolescents in various regions of India. However, there remains a need to develop a comprehensive database on morbidity patterns among adolescents across the country, which would support in formulating policies and developing strategies to improve the well-being of adolescents.

Against this background, the present study was undertaken to determine the morbidity profile of adolescent boys and girls in the rural field practice area of the rural health training center (RHTC), as well as to assess menstrual practices among adolescent girls. Understanding the morbidity pattern will help the investigators identify the challenges in existing government strategies aimed at improving adolescent health.

Materials and Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in the rural field practice area of a medical college in Bangalore, after obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (SIMS & RC/IECC/062012).

A universal sampling technique was adopted covering all the schools, including the one pre-university college located in the field practice area. The sampling frame consisted of nine schools with 331 students in Classes 5-7, two schools with 412 students in Classes 8-10, and one pre-university college with 169 students. In total, 912 students were eligible for the study, of which seven students were excluded as they remained absent from school on two separate visits. Thus, 905 students constituted the final study sample.

After obtaining consent from the parents or guardians of the study subjects and assent from all participants, data were collected using a pretested questionnaire. Information on socio-demographic characteristics, history of any health issues in the past three months, and for girls, menstrual history and practices during menstruation was collected. Data collection was carried out in 2019 by a team comprising of investigators, postgraduates, and interns from the medical college.

Anthropometric measurements such as weight, height, and Body Mass Index (BMI), visual acuity using Snellen’s chart, and haemoglobin estimation using HemoCue 201+ system. were recorded following standard guidelines.6,7,8 The degree of anaemia was graded according to WHO criteria (haemoglobin <11.9 g/dL for non-pregnant women aged 15-45 years and <12.9 g/dL for men above 15 years).9 Psychological assessment was performed using the Adolescent Wellbeing Scale.10

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel 2010 spreadsheet and subsequently analyzed using SPSS (trial version20). Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentages) were used whenever appropriate. Associations between variables were studied using the Chi-square test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant, and <0.001 was considered highly significant.

Results

In the present study, a total of 905 adolescents were included from 11 schools and one pre-university college. Among them, the majority (45.6%) were in middle adolescence (14-16 years), followed by 32.6% in early adolescence (10-13 years) and 21.8% in late adolescence (17-19 years). The proportion of girls and boys was almost equal (girls: 50.2% ; boys: 49.8%). Sociodemographic characteristics showed that 66.4% of the participants belonged to nuclear families, and 83.5% were Hindu by religion (Table 1)

A majority of the study participants (46.5%) reported skin-related problems such as acne, itching, rashes, and dryness. This was followed by dental caries (43.3%) and refractive errors (33.9%). Other health-related problems observed included a history of passing worms, respiratory tract infections, ophthalmic problems, urinary tract infections, diarrhea, ear wax, headache, minor injuries, and generalized fatigue (Figure 1).

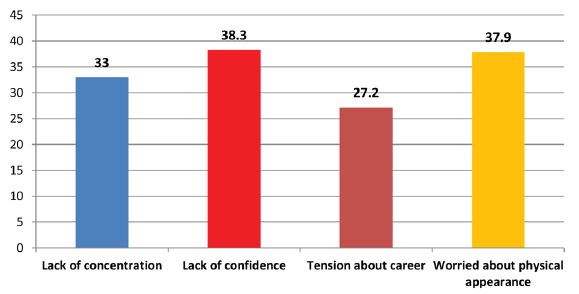

Among the psychological problems observed, 38.3% of participants reported a lack of confidence, 37.9% were concerned about their physical appearance, 33.3% experienced difficulty concentrating on school activities, and 27.2% felt tension regarding their future careers (Figure 2).

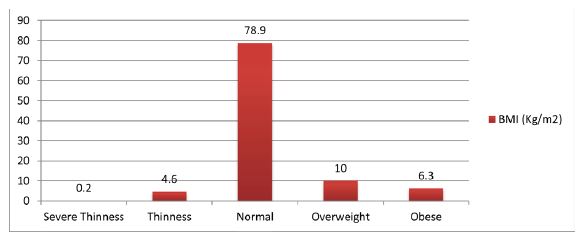

In the current study, 78.9% of adolescents were within the normal BMI range, 6.3% were classified as obese, and 4.8% were underweight (Figure 3).

Based on haemoglobin levels, 63.1% of adolescents were within the normal range (Hb ≥12g/dL for non-pregnant women aged 15-45 years and ≥13g/dL for men above 15 years), while 36.9% were anaemic.9 With respect to gender, severe and mild anaemia were more common among girls (severe: 8.4%; mild: 10.6%), whereas moderate anemia was more prevalent among adolescent boys (28.6%). This difference was found to be statistically significant (P <0.001).

Out of 905 adolescents, only 20.7% reported consuming the weekly iron and folic acid tablets and albendazole tablets provided at school. None of the students reported taking iron, folic acid, or albendazole tablets during school vacations.

In this study, among the 454 adolescent girls, 77.9% had attained menarche and 59.5% were aware of menstruation before menarche. A total of 81.4% reported having regular cycles, and 63.6% experienced dysmenorrhea. Only 34.5% of girls followed satisfactory practices for cleaning the external genitalia (using soap/ antiseptic and water). Among the 270 adolescent girls who were aware of menstruation before menarche, the major source of information was family members (70%), followed by friends (19.3%) and other sources (10.7%) (Table 2).

Most of the girls used sanitary pads as absorbent (248; 70.1%), while 106 (29.9%) used cloth. The most common method of disposal was burying the absorbent (134; 37.8%), followed by disposal in a separate dustbin (104; 29.4%). About 65 (18.4%) girls discarded with routine waste, and 51 girls (14.4%) burnt the absorbent. A total of 153 (43.2%) adolescent girls were aware of the free sanitary napkins provided by the government (Table 3).

Discussion

Adolescents are often perceived as a healthy population because mortality rates in this age group are lower than those of young children and older adults. However, there are several interrelated reasons why close attention must be paid to adolescent health. It would help reduce current mortality and morbidity, lowers the burden of disease in later life, represents an investment in both present and future well-being, supports fulfilment of human rights, and contributes to protection of human capital.3

In the present study, the majority of participants were in the middle adolescence phase (14-16 years: 45.6%), followed by early adolescence (32.6%) and late adolescence (21.8%).

The number of adolescent girls and boys was nearly equal. In contrast, studies by Gupta et al.,in Chandigarh among 854 adolescents and by Kotecha PV et al., among 768 adolescents in Vadodara district reported a higher proportion of males (63% and 44%, respectively). A cross-sectional study conducted by Sajna MV et al., in Thrissur among 380 school students during 2014-2015 reported that 94.2% were girls and only 5.8% were boys.11,12,13 This reflects a changing trend in gender-related literacy status.

In the current study, the majority of participants belonged to the nuclear families (66.4%). Similar findings were reported in a cross-sectional study by Priya SH et al., among 240 school children in rural Puducherry and in the study conducted in Thrissur by Sajna MV et al.,among 380 school students.13,14

In the present study, the most commonly reported morbidity was skin-related problems (46.5%), followed by dental caries (43.3%) and refractive errors (33.9%). In a study conducted by Bhattacharya A et al., among 424 adolescents in West Bengal, dental caries emerged as the major morbidity (40.3%), followed by refractive errors (33.49%), skin-related problems (26.6%), and worm infestation (23.11%). Similarly, a study conducted by Yerpude PN et al., in Andhra Pradesh among 210 adolescents aged 10-19 years reported dental caries (41.9%) as the most prevalent morbidity, followed by skin-related problems (20.5%), worm infestation (13.33%), conjunctivitis (11.43%), and respiratory tract infections (10%).15,16

Certain psychological problems were also prevalent among adolescents in our study, similar to the findings reported by R Kumar et al.17

Among the 905 adolescents assessed in the present study, 9.9% were overweight, 6.3% were obese, and 4.8% were underweight. A study by Borker et al., conducted among 100 adolescents in the Rural Primary Centre of Suliya Taluk in Dakshina Kannada district reported that 19% were underweight and only 1% were obese. A much higher prevalence of underweight (74%) was observed in a study conducted by Salunkhe V et al. among adolescents in Navi Mumbai.18,19 The prevalence of undernutrition was considerably lower in the present study than that reported in other studies, which may be attributed to the effective implementation of nutritional health programs in the study area. The overall prevalence of obesity in our study was lower (16.2%) than that reported by S Seema et al., (23.9%) among 385 adolescents in Rohtak district, Haryana.20

The overall prevalence of anaemia in the current study was 37%. A high prevalence of anaemia was reported in studies conducted by Verma R et al., (67.7%) among 1650 adolescents in Rohtak district and by Agarwal AK et al.,(59.58%) among 900 school-going adolescents in Bareilly.21,22 In contrast, a much lower prevalence of anaemia (15.69%) was observed in a study conducted by Shinde M et al., among 688 adolescents in rural areas of Madhya Pradesh.23 In the present study, the prevalence of mild (10.6%) and severe (8.4%) anaemia was significantly higher among adolescent girls, while moderate anaemia (28.6%) was significantly more among adolescent boys. Similar results were observed in a study conducted by Agarwal AK et al., and Gupta D et al., both of which documented a higher prevalence of anaemia among females (65.11% and 52.8%, respectively) compared to males. These findings indicate that anaemia is prevalent not only among adolescent girls but also among adolescent boys. Iron requirements are particularly high in boys during peak pubertal development due to increased blood volume, muscle mass, and myoglobin levels.22 Hence, it is necessary to focus on adolescent boys as well.24

The current study reported that only 20.7% of adolescents were consuming weekly iron and folic acid tablets. In a cross-sectional study conducted by Sajna M V et al., in Thrissur among 380 school students , 36.6% students initially took iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets; however, adherence to WIFS (Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation) was only 15%. The WIFS programme is a national initiative by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare to combat anaemia in adolescent girls and boys aged 10-19 years in government, government-aided, and municipal schools from classes 6 to 12.13 The programme provides free, supervised weekly iron and folic acid tablets to all eligible adolescents.25

Another cross-sectional study by Priya SH et al. among 240 school children in rural Puducherry reported that 45.8% of adolescents were consuming IFA tablets regularly.14 This indicates that awareness about consumption of weekly iron and folic acid tablets was poor among the participants in the present study, possibly due to limited knowledge regarding free supply and importance of their consumption during adolescence.

In our study, 77.9% of adolescent girls had attained menarche. Among them, 70.1% were using sanitary pads as absorbents, while 29.9% reported using cloth. The following observations were made in other similar studies (Table 4).

In the present study, the most common method of absorbent disposal was burying (37.8%), followed by disposal in a separate dustbin (29.4%) and discarding with routine waste (18.4%). A study by Thakre SB et al.,reported burning as the predominant method of disposal (52.20%), followed by disposal with routine waste (39.79%).29

Most of the adolescent girls (65.5%) used only water to clean their private parts, while 34.5% used both water and soap/antiseptic. A study conducted by Borkar SK et al. reported that only 39% of girls cleaned their external genitalia with soap and water. Similarly, Thakre SB et al., found that 59.47% of adolescent girls used water with soap/antiseptic, whereas 40.57% used only water.27,29 These findings indicate that the maintenance of personal hygiene during menstrual cycles was unsatisfactory among study participants.

Conclusion

In the present study, the majority of the adolescents reported skin-related problems such as acne, itching, rashes, dryness of skin (46.5%), followed by dental caries (43.3%), refractive errors (33.9%), history of passing worms (30.7%), and respiratory tract infections including cold, cough, fever, difficulty in breathing (30.5%). A smaller percentage of adolescents presented with other morbid condition.

Controlling these morbid conditions and associated risk factors during adolescence is essential to reduce the burden of both communicable and non-communicable diseases in the future. This can be achieved by conducting regular health check-ups for school-going adolescents.

The morbidity status of adolescents can be improved through health education on balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, and avoidance of risky behaviors; improving access to affordable and quality healthcare through strengthened services under SNEHA clinics; supporting those facing psychosocial problems through trained counselors; and reinforcement of community-based health programs to reach underserved populations and promote health awareness.

Although adolescents are considered as a healthy segment of the society, the findings from the present study and other research indicate that many suffer from one or more morbid conditions, that are largely treatable when detected early.

Conflict of Interest

Nil

Supporting File

References

1. World Health Organization. Adolescent health: Overview and impact [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 11]. Available from: https:// www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health.

2. National Health Mission. Adolescent health [Internet]. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; [cited 2025 Apr 14]. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/index1. php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=818&lid=22.

3. World Health Organization. Adolescents: health risks and solutions [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www. who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescents-health-risks-and-solutions.

4. Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Anaemia Mukt Bharat [Internet]. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2022 [cited 2025 Nov 28]. Available from: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage. aspx?PRID=1795421®=3&lang=2.

5. Kumar R, Chaudhary SS, Nagargoje MM, et al. Morbidity pattern and socio-demographic profile of adolescents attending public and private schools in Agra city. Int J Med Pub Health 2024;14(4);216- 220.

6. World Health Organization. BMI-for-age (5-19 years) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; [cited 2025 Feb2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/toolkits/ growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/indicators/ bmi-for-age.

7. Azzam D, Ronquillo Y. Snellen Chart. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

8. HemoCue. HemoCue 201+ operating manual [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Feb 2]. Available from: https://stat-technologies.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Hb-201-DM-Operation- Manual.pdf.

9. World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anemia and assessment of severity [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; [cited 2025 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www. who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.1.

10. Adolescent well-being scale [Internet]. 2019; [cited 2025 Feb 2]. Available from: https://youthrex. com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Adolescent- Wellbeing-Scale.pdf.

11. Gupta M, Bhatnagar N, Bahugana P. Inequity in awareness and utilization of adolescent reproductive and sexual health services in union territory, Chandigarh, North India. Indian J Public Health 2015;59:9-17.

12. Kotecha PV, Patel S, Baxi RK, et al. Reproductive health awareness among rural school going adolescents of Vadodara district. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS 2009;30(2):94-9.

13. Sajna MV, Jacob SA. Adherence to weekly iron and folic acid supplementation among the school students of Thrissur corporation – a cross-sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Health 2017;4(5):1689-94.

14. Priya SH, Datta SS, Bahurupi YA, et al. Factors influencing weekly iron folic acid supplementation programme among school children: Where to focus our attention?. Saudi J Health Sci 2016;5(1):28-33.

15. Bhattacharya A, Basu M, Chatterjee S, et al. Nutritional status and morbidity profile of school-going adolescents in a district of West Bengal. Muller J Med Sci Res 2015;6:10-5.

16. Yerpude PN, Jogdand KS, Jogdand M. A study of health status among school going adolescents in South India. Int J Health Sci Res 2013;3(11):8-12.

17. Kumar R, Prinja S, Lakshmi PVM. Health care seeking behavior of adolescents: Comparative study of two service delivery models. Indian J Pediatr 2008;75(9):895-899.

18. Borker S, Pare J, Anitha C, et al. Nutritional status of adolescents at a rural health centre of Dakshina Kannada district of Karnataka. MRIMS J Health Sciences 2015;3(2):227-230.

19. Salunkhe V, Sutrawe A, Goel R, et al. Health status of adolescent in Navi Mumbai. International Journal of Medical and Clinical Research 2011;2(1):14-19.

20. Seema S, Rohilla KK, Kalyani VC, et al. Prevalence and contributing factors for adolescent obesity in present era: Cross-sectional Study. J Family Med Prim Care 2021;10(5):1890-1894.

21. Verma R, Kharb M, Yadav SP, et al. Prevalence of anemia among adolescents under IBSY in rural block of Dist. of Northern India. International Journal of Social Science and Interdisciplinary Research 2013;2(9):95-106.

22. Agarwal AK, Joshi HS, Mahmood SE, et al. Epidemiological profile of anaemia among rural school going adolescents of district Bareilly, India. Ntl J Community Med 2015;6(4):504-507.

23. Shinde M, Trivedi A, Joshi A. Morbidity pattern among school children of rural area of Obaidullaganj block of Raisen District of Madhya Pradesh. Int J Adv Med 2015;2(2):144-6.

24. Gupta D, Pant B, Kumari R, et al. Screen out anaemia among adolescent boys as well! Natl J Community Med 2013;4(1):20-5.

25. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation (WIFS) Programme [Internet]. New Delhi: National Health Mission; 2012 [cited 2025 Feb]. Available from: https://nhm.gov.in/index1. php?lang=1&level=3&sublinkid=1024&lid=388.

26. Shanbhag D, Shilpa R, D‘Souza N, et al. Perceptions regarding menstruation and Practices during menstrual cycles among high school going adolescent girls in resource limited settings around Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health 2012;4(7):1352-1362.

27. Borkar SK, Borkar A, Shaikh MK, et al. Study of menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent girls in a tribal area of Central India. Cureus 2022;14(10):e30247.

28. Jailkhani SMK, Naik JD, Thakur MS, et al. Patterns & problems of menstruation amongst the adolescent girls residing in the urban slum. Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences 2014;2(2):529-534.

29. Thakre SB, Thakre SS, Reddy M, et al. Menstrual hygiene: Knowledge and practice among adolescent school girls of Saoner, Nagpur district. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2011;5(5):1027- 33.